Niclas Hammarstr?m/Kontinent/ZUMA)

Niclas Hammarstr?m/Kontinent/ZUMA)

The fighting lasted several hours. Two local militias, the Khabur Guards and the Syriac Military Council, fought to defend their countrymen. In Tel Hormuz, where the resistance was strong, 11 were killed and a good number went missing. Women distinguished themselves with their courage. Still, the Christian fighters were overwhelmed. The military superiority of ISIS was obvious and defeat was inevitable.

Related: Attacks on Assyrians in Syria By ISIS and Other Muslim Groups

Related: Timeline of ISIS in Iraq

Everything began 10 days before the invasion, when ISIS ordered the villagers to remove crosses from their churches and pay a special poll tax. The villagers refused. The overall goal of ISIS was to expel these "infidels" from the country and extend its hegemony to the region. This was a repeat of the religious cleansing operation that took place in the summer 2014, on the other side of the border, in the Ninevah Plains region in Iraq.

"They had been training for a year to invade the villages," says Guiwargis (not his real name) a survivor who later fled to Lebanon. "ISIS had plans and maps. The jihadists implemented a concerted and deliberate strategy to empty the region of its Christians."

As ISIS advanced, the Syrian army — which had vowed to protect its minorities — seemed to disappear. Free Syrian Army rebels were nowhere to be seen either. Kurdish military forces, in contrast, confronted the jihadists at times but withdrew from certain villages, abandoning the Christians, according to former inhabitants.

Victorious, the jihadists assembled their "spoils of war": more than 220 people — including children and seniors — captured from Assyrian villages along the Khabur. Even the 80-year-old mayor of the village Tel Shamiran was arrested with his wife and family. Male and female prisoners were separated and forced to wait in a torrential rain before being deported to another village. Then, the hostages were piled on top of each other in vehicles like livestock to be transferred to a nearby city.

"On the sixth day of our captivity, Widad Yonan, a 48-year-old woman who had resisted ISIS troops during the invasion of her village, was taken to an unknown place to most likely be executed," Guiwargis recalls.

For seven months, they were kept in a large room that was formerly a Syrian police station. The premises were equipped with screens to teach prisoners about the Koran and Muslim jurisprudence. "We were taught the lessons of the Koran and urged to convert to Islam. The main instructor was Saudi ... We all refused," Guiwargis says.

In the courtyard there were also Uzbeks, Iraqis, Turks, Tunisians, Turkmens, Egyptians, Algerians and Syrians. The guards were Tunisians. Sometimes, coalition raids would target the area.

One day, the main local emir for ISIS, a one-eyed Iraqi rumored to be Saddam Hussein's former officer, ordered that the three most beautiful girls be brought to him so that he could choose one. Caroline Shlimoun, a 14-year-old girl from Tel Jazira village, was torn from her family. Since then, her parents have had no news of her. The emir most likely married her by force before bringing her to Raqqa, the Syrian capital of the jihadists, to mother a child.

"Her father and mother have not lost hope of finding her," says Auchana (not his real name), another survivor.

The religious pressure exerted on the prisoners was constant. They were accused of being infidels and threatened with death. "We were told that killing us is lawful," says Auchana. "One morning they came to select six of us under the false pretext of going to Al-Hassakeh to negotiate our release in exchange for ransom paid by the Assyrian Bishop Mar Aprim Athniel. I was part of the lot."

That was the day of Eid al-Adha, the feast of sacrifice. The hostages were led into the desert for a show of Islamic justice. They wore orange outfits. A "judge" verified the "legality" of the sentence and ordered it to be carried out immediately: death! "Three of our companions were killed before our eyes on Sept. 23, 2015," Auchana recalls. "We had to carry their dead bodies to a truck. I don't know where they were buried."

These dour scenes, which ISIS filmed and broadcasted, marked a tipping point for the abducted Christians. The videos created an international shock wave and led to negotiations to pay a ransom for the hostages, who were transported to Raqqa.

"We were moved blindfolded all the way. In Raqqa, we no longer saw the sun," Auchana explains. "We were locked up in an underground prison. Three days later, the Russians started bombing the city. The guards asked us whether we had ties to the Russian Church. We replied that we were Assyrians and followers of the Eastern Church."

Discreetly, negotiations took place via smugglers who had settled on the Iraqi-Syrian border.

Around the world, the Assyrian diaspora mobilized to raise funds that were given to Mar Aprim Athniel, the tireless Assyrian bishop. Donations came from Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia. Volunteers transported the money to Iraq and Syria. Solidarity demonstrations like the one that took place in Sarcelles, France, on March 1, 2015, were organized.

"Without this generous help, we would have experienced a fate similar to that of our three compatriots. Death, in other words. Except of course for the women and children, who are considered of value to ISIS because they can be sold as slaves," says Guiwargis.

In August 2015, ISIS began releasing children, women and men for ransoms of $30,000 per person. The six-stage process of release ended Feb. 22, 2016, exactly one year after the mass abduction. In total, the captors were paid more than $500,000.

The Assyrians of Khabur are descents of one of the world's oldest Christian communities. They belong to the Church of the East, also known as the Nestorian Church, and are the children of families deported from Iraq after the Simele massacre of 1933. Before that, in 1915, the Assyrians were the target of a genocide under the Ottoman Empire.

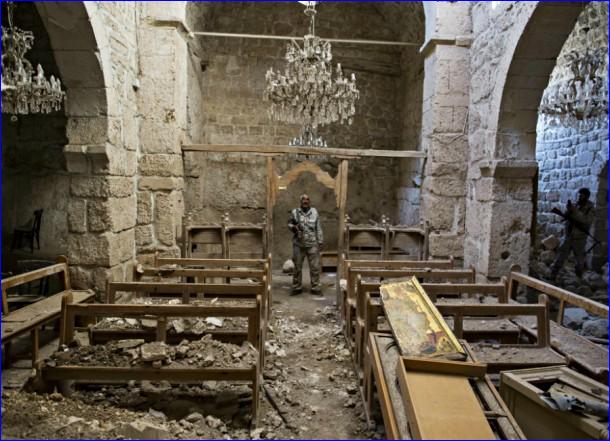

The Simele survivors were settled in Syria's Khabur region by French authorities, who controlled the country at that time. The northeast of Syria, with its rosary of villages on both banks of the Khabur, was their second country of refuge. ISIS has now abandoned the area. But it is still almost completely void of inhabitants. Houses are plundered, churches completely destroyed, public buildings burned.

Guiwargis returned to his village of Tel Shamiran only to find ruins. Broken hearted, he went back to Lebanon. He, like the other survivors, must look for a host country. Australia, perhaps. A number of survivors have already taken the road to exile, joining others in Europe, the United States and Canada. One Assyrian woman, currently a refugee in Germany but with plans of going to Australia, summarizes this new tragedy: "It is a wound that will never be healed," she says. "Now we're going to the land beyond the sun."

or register to post a comment.