According to UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, Assyrian is among 18 languages or dialects in Turkey that have either disappeared or are at risk of extinction. Community estimates place the country's Assyrian (Aramean--Assyrian--Chaldean) population between 15,000 and 20,000 people. Roughly 15,000 live in Istanbul and nearby cities, while most of the remainder reside in Merde (Mardin) and Sirnak provinces, particularly in the Tur Abdin region, historically a stronghold of Assyrian Christianity.

The last Assyrian school in Merde closed in 1928, leaving the community without formal education in its mother tongue for decades.

That changed in 2014 following a legal battle. The Assyrian Ancient Meryem Ana Church Foundation in Istanbul sought to open a kindergarten in 2013 but was blocked by the Ministry of National Education. The Ankara 13th Administrative Court overturned the ministry's decision, paving the way for the opening of the Mor Efrem Assyrian Kindergarten, which remains the only school in Turkey where Assyrian is formally taught.

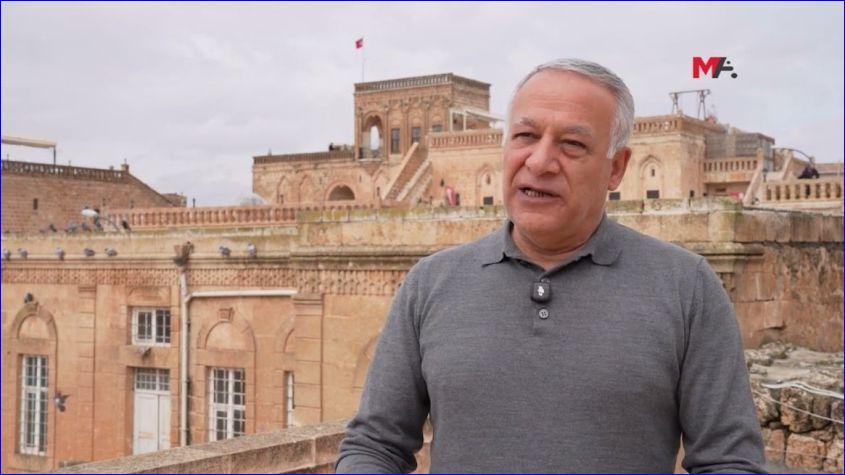

Speaking to Mezopotamya Agency, Evgil Türker, President of the Assyrian Associations Federation (SÜDEF) based in Medyad (Midyat), said, "There is no other school." Ahead of International Mother Language Day on 21 February, Türker described the language's decline as both rapid and deeply concerning.

"Assyrian once spread across Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, and almost all of Turkey," he said. "It influenced many other languages and made important contributions to Arabic. But today it faces a serious danger."

As Arabic became dominant across much of the Middle East, many Assyrian (Aramean--Assyrian--Chaldean) people gradually shifted away from their ancestral language. "In Syria, Lebanon, Iraq -- even in some parts of Turkey -- Assyrian was replaced by Arabic," Türker said. "Today, I would say that 80 percent of Assyrians from Syria speak Arabic as their mother tongue."

Emigration has further accelerated the decline. Beginning in the 1980s, large numbers of Assyrians left southeastern Turkey, many emigrating to Europe. As communities shrank, so did the everyday use of the language.

"In the Botan region, Assyrian was once the strongest spoken language," Türker said. "In Medyad, even Kurdish families who had lived there for 150 or 200 years spoke Assyrian. It was the dominant language in the market, in the streets, and in schools."

Today, he said, that reality has reversed. "Our children speak Turkish among themselves. When I started school in 1972, I did not know a single word of Turkish."

Historically, the language survived through religious institutions. Monasteries served as centers of theology, philosophy, mathematics, and literature, while the medrese system provided religious and linguistic education. However, after decades of emigration and institutional weakening, those structures have lost much of their reach.

Under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, non-Muslim communities in Turkey were recognized as minorities with certain educational rights. Assyrian leaders argue that these protections should be more fully extended to their community.

"If we are citizens, if we have this right, and if Lausanne is considered one of the most important agreements, then the state must uphold it," Türker said. "If the Ministry of National Education has a budget, there should be a budget for these schools as well."

He also called on local governments to revive earlier initiatives promoting multilingualism. In 2014 and 2015, some municipalities in southeastern Turkey adopted a "multilingual municipality" model reflecting the region's linguistic diversity, including Assyrian, Turkish, Kurdish, and Arabic. Those efforts stalled in subsequent years amid political changes and the appointment of state trustees in place of elected mayors.

"Medyad speaks four languages," Türker said. "Multilingual governance is not a slogan here. It is a reality."

For now, the Mor Efrem kindergarten remains a singular experiment -- a modest classroom carrying the weight of centuries.

"If we do not open a school in Medyad, in the heart of Tur Abdin, and provide education in our mother tongue," Türker said, "we will disappear."

or register to post a comment.