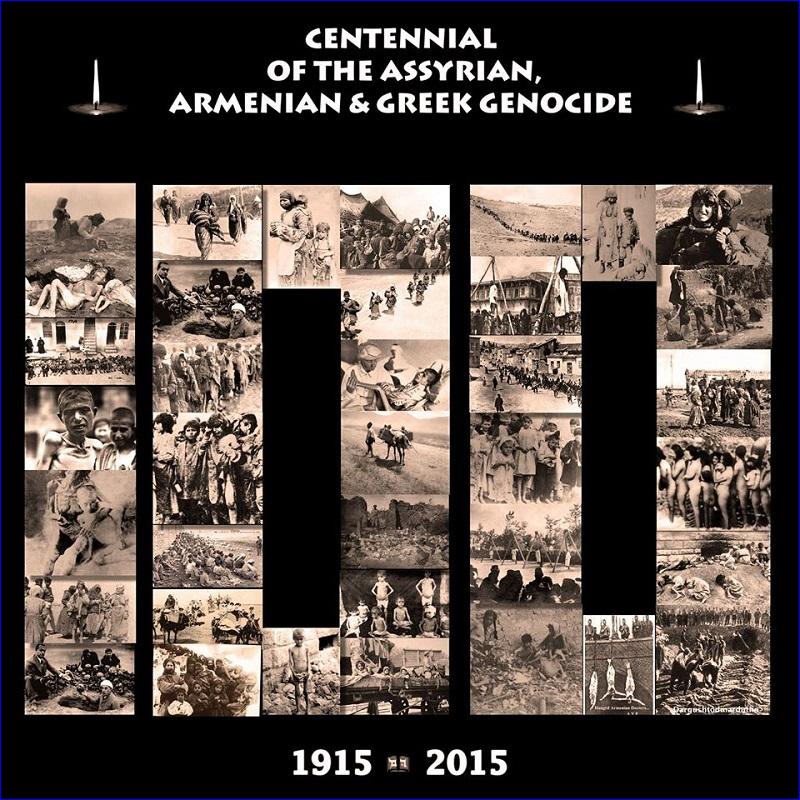

By adopting a comparative framework, the editors seek to overcome the historiographical fragmentation that has traditionally separated the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian cases and to analyze them instead as interconnected manifestations of a sustained genocidal process. In doing so, the volume aligns with and builds upon earlier scholarship by Taner Akçam [1], Benny Morris and Dror Ze'evi [2], George Shirinian [3], and others, who have argued for an "ecumenical" approach to late Ottoman state violence--one that recognizes shared structures, ideologies, and mechanisms without collapsing distinct victim experiences.

Content

The preface establishes the volume's central historiographical intervention: the study of the genocide of Ottoman Christians as a long-term and multi-phased process carried out by successive regimes representing a relatively stable ruling elite. Rather than focusing exclusively on 1915, the editors emphasize continuity from the late nineteenth century through the early Republican period, thereby normalizing the use of terms such as "Ottoman genocide" within scholarly discourse. While the Armenian Genocide has long dominated scholarly discourse, the editors argue that this focus has marginalized Greek and especially Assyrian experiences. The volume thus contributes to comparative genocide studies by integrating diverse archival materials, survivor testimonies, and theoretical approaches across national and disciplinary boundaries.

The volume opens with an introductory chapter by Taner Akçam, who proposes the concept of an "Ottoman Genocide" unfolding between roughly 1876 and 1924. Akçam distinguishes between a long-term genocidal process and discrete genocidal moments, situating the Armenian Genocide as its most intense manifestation rather than an isolated event. His framework rests on three interrelated dynamics: persistent Muslim--Turkish intolerance toward non-Muslims, the destabilizing transition from empire to nation-state, and a recurring cycle of reform demands, massacres, foreign intervention, and territorial secession. This conceptualization is one of the volume's major strengths, even where its application across cases remains uneven.

Subsequent chapters are organized into three thematic sections, each containing three to five contributions. Part I focuses on documentation and historical perspectives, introducing previously unused archival sources from Greek, American, French, German, and Polish contexts. These studies illuminate local and international dimensions of anti-Christian violence and reassess the roles of state actors, foreign observers, and military planners. Part II addresses memory, recognition, and denialism, with particular emphasis on the late internationalization of the Assyrian Genocide, survivor memory, diasporic cultural production, and the mechanisms of Turkish state-sponsored denial. Part III examines legal and human-rights dimensions, situating the genocides within early international legal discourse, contemporary human-rights frameworks, and efforts by institutions such as the League of Nations to address the aftermath, particularly concerning women and children.

While these chapters collectively enrich the empirical base of Ottoman genocide studies, this review focuses primarily on the two contributions that address the Assyrian Genocide, which remain among the least studied components of this historical process.

In David Gaunt's "Late Recognition of the Assyrian Genocide," the author investigates why the mass destruction of Assyrians during World War I -- despite its scale and extensive contemporary documentation -- remained largely unrecognized for much of the twentieth century. Gaunt estimates that up to half of the Assyrian population of the Ottoman and Persian Empires perished through mass killings, forced displacement, and destruction, yet the genocide failed to gain sustained international or communal acknowledgment in the immediate post-war period.

Gaunt frames his analysis through the sociological theory of collective trauma, emphasizing that recognition depends not merely on historical fact but on the presence of a cohesive "carrier group" capable of producing and disseminating a unified narrative of catastrophe and identifies structural fragmentation as a central obstacle to recognition. He argues that the Assyrian case failed to meet these conditions for nearly sixty years, resulting in what he terms a prolonged period of silence from the 1920s to the 1980s.He demonstrates how Assyrian recognition efforts were undermined by internal fragmentation along ecclesiastical, linguistic, and regional lines, institutional silence -- particularly from the Syriac Orthodox Church supposedly seeking to protect remaining communities in Turkey -- and geopolitical marginalization after the Treaty of Lausanne. As a result, memory of the genocide survived primarily through family oral traditions, songs, and village narratives, rather than through public commemoration or historical writing. Though, existing narratives were geographically limited, confessional in perspective, or politically ineffective. No authoritative "master narrative" emerged that could unify western and eastern Assyrians, define perpetrators clearly, or mobilize broader international sympathy.

Gaunt identifies a turning point in the late twentieth century with the growth of the Assyrian diaspora in Europe, particularly from Tur Abdin, beginning in the 1960s and accelerating in the 1970s. Central to this process was the revival and standardization of the term Sayfo ("the year of the sword") as a unifying concept for the genocide, and increased scholarly engagement, which together enabled the gradual internationalization of Assyrian genocide memory.

From the late 1990s onward, academic scholarship expanded significantly, incorporating archival research, sociological analysis, and legal perspectives. At the same time, Assyrian activists adopted a new strategy of coalition-building with Armenian and Greek organizations, amplifying political lobbying efforts and increasing their effectiveness in securing parliamentary recognitions.

Mary Akdemir's "Big Secrets, Small Villages" complements Gaunt's institutional and political analysis by examining the cultural transmission of genocide memory, particularly through music, oral history, and attachment to place among Assyrians from the Tur Abdin region. Rather than focusing on political recognition or institutional silence, Akdemir centers on everyday cultural practices--especially diaspora music--as key vehicles of collective memory and intergenerational trauma.

The chapter opens with the case of Azakh, a village whose inhabitants famously resisted Ottoman and Kurdish forces in 1915 but whose last Assyrian residents fled in the 1990s amid continued persecution. Akdemir uses this example to illustrate how physical separation from ancestral lands has not severed memory; instead, it has intensified symbolic attachment. Drawing on Pierre Nora's concept of lieux de mémoire ("sites of memory"), she argues that Assyrian villages, churches, and landscapes function as repositories of genocide memory, even when Assyrians themselves are no longer physically present. Akdemir situates her analysis within a concise historical overview of Assyrian identity, emphasizing the centrality of Christianity, language (Turoyo/Surayt and Syriac), and territorial rootedness in Tur Abdin.

A core contribution of the chapter is its analysis of Assyrian music as an archive of collective trauma. Building on Naures Atto's work on oral transmission, Akdemir analyzes songs circulated via YouTube and diaspora media to demonstrate how genocide memory is passed down across generations.

Through detailed analysis of diaspora songs and survivor testimonies -- especially those related to the village of Iwardo (Ayn Wardo) -- she argues that collective memory encompasses not only trauma and loss but also narratives of resistance and heroism. Akdemir further situates these cultural practices within the context of post-genocide Turkification policies, linguistic repression, and ongoing denial, framing Assyrian music as both commemoration and political critique.

Brief Assessment

The volume's principal strength lies in its comparative and integrative approach, which advances genocide studies beyond nationally segmented narratives. Akçam's conceptual framework provides a coherent analytical backbone, while the diversity of sources -- particularly diplomatic and oral materials -- adds significant empirical depth. Chapters drawing on missionary accounts, diplomatic correspondence, and League of Nations records underscore the importance of Western witnesses in documenting atrocities and contesting denial. The engagement with memory politics -- especially the cycles of remembrance, suppression, and rediscovery explored in the Assyrian-focused chapters -- adds a valuable cultural and sociological dimension to the historical analysis.

The sections dealing with legal responsibility, mens rea, and postwar justice significantly strengthen the volume's contribution to genocide and human-rights studies. By examining early efforts to conceptualize "organized and premeditated collective crime" and to prosecute perpetrators, these chapters illuminate the long-term implications of Ottoman atrocities for international law and contemporary human-rights discourse.

Within the broader field of genocide studies, this volume contributes to ongoing efforts to contextualize the Armenian Genocide alongside parallel campaigns against Greeks and Assyrians. It aligns with recent scholarship that emphasizes process, continuity, and regional interconnectedness, while also addressing long-standing gaps in Assyrian genocide research. By foregrounding memory, denial, and cultural transmission, the book bridges historical analysis with sociological and cultural approaches increasingly central to genocide scholarship.

Concluding Remarks

The Genocide of the Christian Populations in the Ottoman Empire and Its Aftermath is a significant and timely contribution to comparative genocide studies. Its greatest value lies in its insistence on studying the destruction of Ottoman Christian communities as a unified historical process and in its inclusion of underrepresented Assyrian perspectives. The chapters by David Gaunt and Mary Akdemir are especially compelling, offering complementary insights into the politics of recognition and the Assyrian cultural afterlives of genocide. They deepen our understanding of how genocide is remembered, silenced, and resisted across generations.

The volume will be of considerable interest to scholars and graduate students in genocide studies, Ottoman history, memory studies, and human rights, and it provides a strong foundation for future research on the Assyrian Genocide and its place within the broader history of mass violence in the late Ottoman world.

Notes:

[1] Taner Akçam, Ermeni Soykırımı'nın Kısa Bir Tarihi (A Short History of the Armenian Genocide), Aras: Istanbul, 1921; see my review: https://seyfocenter.com/english/review-of-taner-akcams-new-book-a-short-history-of-the-armenian-genocide/

[2] Benny Morris and Dror Ze'evi, The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities 1894-1924, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2019

[3] George Shirinian (Ed.), Genocide in the Ottoman Empire: Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks 1913-1923, Berghahn Books: New York, 2017

or register to post a comment.