Related: The Assyrian Genocide

Dr. Bengaro's study analyzes the role of the German Orientalist Max von Oppenheim (1860-1946) and the Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient (NfO) as key institutions of German "Orientpolitik." Founded in September 1914, this was a central organization in the field of jihadization and war propaganda. Using archival sources and contemporary writings, the study reconstructs the emergence, ideological foundation, and operational implementation of so-called "jihad propaganda." It shows how the jihad call of November 14, 1914, was conceived as a religiously legitimized means of pursuing strategic goals that went far beyond the religious sphere.

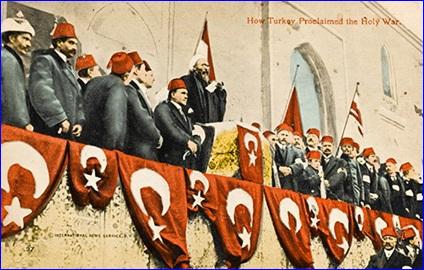

On behalf of the Sultan, Ürgüplü Hayri, Sheikh of Islam and supreme religious authority of the Caliphate, read out the five-part jihad fatwa on November 14, 1914, in the Great Mosque of Mehmed the Conqueror in Constantinople.

Related: 750,000 Assyrians were killed in the Turkish Genocide in 1915-1918

In addition, the interaction between Pan-Islamism and Pan-Turkism is examined, in particular the instrumentalization of the religious and nationalstic ideologies for internal Ottoman power consolidation and rigorous ethnic-religious homogenization. The call to jihad, which officially served to mobilize Muslims against the enemies of the empire, became an ideological instrument of state-tolerated violent politics within the empire. Under the guise of "holy war," Christian minorities--Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks--were effectively declared outlaws, leading to systematic expulsions, massacres, and campaigns of extermination.

The author argues that although propaganda jihad had little effect in the colonial territories of the Allies, it acted as a catalytic mechanism in the Ottoman Empire, radicalizing religious and national tensions. In conjunction with Pan-Turkic ideas, it served as an ideological justification for the ethnic cleansing and extermination of Christian populations--processes that are now internationally recognized as the first genocide of the 20th century.

Overall, the study contributes to the understanding of the intertwining of religion, nationalism, and violent politics in the early 20th century and shows how religious rhetoric was instrumentalized in times of war to legitimize mass crimes. In doing so, it opens up new perspectives on the ambivalence between religious mobilization, geopolitical calculation, and propagandistic manipulation in warfare.

The following interview with Dr. Sabro Bengaro was conducted the day he successfully defended his PhD thesis.

Abdulmesih BarAbraham (AB): First of all congratulations on successfully defending your PhD thesis. Your hard work and dedication have truly paid off.

What particularly motivated you about the connection between German foreign policy and Islamic mobilization during the First World War? As far as I know, it was the German Orientalist Gabriele Yonan who addressed the topic in 2000 with an article entitled Holy War Made in Germany: New Light on the Holocaust Against the Christian Assyrians during World War I.

Dr. Sabri Bengaro (SB): Thank you for your congratulations. As you know, like yourself, I was born in Tur Abdin, a region historically characterized by its division between Christian and Muslim communities. From an early age, I was aware of the tensions that existed between these groups, although I did not initially comprehend their underlying causes. These tensions, as I later came to understand, were rooted in fundamental aspects of Islamic doctrine. According to classical Islamic jurisprudence, societies are traditionally classified into two distinct spheres: Dar al-Islam ("the abode of Islam" or "the abode of peace") and Dar al-Harb ("the abode of war"). This dichotomy forms the basis of Islamic conceptions of war and peace, as reflected in the Qur'anic verse, "God calls to the abode of peace" (Qur'an 10:25). Within such a framework, the dehumanization of non-Muslims often becomes a normalized and legitimized social reality.

The division of societies into opposing categories of "us" and "them" represents a profound social and moral problem. As Dr. Gregory H. Stanton, the founding president and chairman of Genocide Watch, has observed, this process of categorization constitutes one of the early stages in the progression toward genocide. Testimonies from survivors of genocide further reveal that Islamic ideology played a significant role in motivating ordinary individuals--Kurds, Turks, and other Muslims--to participate in the massacres of Assyrians. These accounts marked a turning point in my intellectual development and prompted me to investigate more deeply the relationship between Islam and mass violence, with particular attention to the declaration of Jihad in 1914.

AB: What new aspects did your research reveal in this context?

SB: My research revealed that the proclamation of Jihad in the Ottoman Empire elicited critical responses from contemporary observers. Notably, the Dutch Orientalist Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje (1857--1936) characterized this declaration as a product "made in Germany" in a study published in 1915, highlighting the instrumental role of German influence in its formulation. Consequently, Germany's involvement in the Jihad declaration should be understood as an integral component of its broader political and military strategy during the First World War.

Meanwhile, many Western and Turkish historians, whose analyses focus on Germany's strategic objectives, have tended to interpret the Jihad declaration as a failure or an ineffective initiative. However, such interpretations offer an incomplete understanding of its broader consequences. As I argue in my dissertation, the Jihad declaration functioned as a catalyst that incited segments of the Muslim population to commit acts of violence against non-Muslims in the country, namely Christian Assyrians, Armenians, and Greeks. In this context, it contributed to the Young Turk regime's efforts to achieve the demographic and ideological homogenization of the Republic of Turkey.

AB: Did you investigate Max von Oppenheim's Memorandum concerning the fomenting of revolutions in the Islamic territories of our enemies, who was the mastermind behind the jihadization policy?

SB: Max von Oppenheim, the German "diplomat," and archaeologist, played indeed a pivotal role in formulating and advancing Germany's islamic policy in the early twentieth century. Having resided for extended periods in Egypt and various regions of the Middle East, he cultivated close connections with the Ottoman elite and became instrumental in facilitating the Ottoman Empire's declaration of Jihad during the First World War. His prominent involvement in these efforts earned him the epithet Abu Jihad (father of Jihad).

Preceding Oppenheim's initiatives, Kaiser Wilhelm II had already established cordial relations with Sultan Abdulhamid II and undertook state visits to Constantinople, Damascus, and Jerusalem. During his address in Damascus, Wilhelm proclaimed himself the protector of the world's three hundred million Muslims--a gesture that contributed to his being popularly referred to as Hajji Wilhelm.

AB: To what extent was your work also an examination of the relationship between ideology and power politics?

SB: Indeed, my research investigates the interdependence of ideology and power politics, showing that frameworks such as pan-Islamism and Jihad were not merely instruments of political expediency but integral to the formulation of state strategy. By examining diplomatic correspondence, propaganda, and policy documents, it demonstrates how ideological discourse both reflected and actively shaped the exercise of political power within the Ottoman--German alliance. In doing so, the study reveals that ideology and power were mutually constitutive, each reinforcing and redefining the other.

AB: Let us move to sources and methodology. What types of sources (e.g., diplomatic correspondence, propaganda writings, archival documents) did you use to reconstruct German "jihad policy"?

SB: In reconstructing German "jihad policy," I started with Max von Oppenheim's Memorandum, which served as a key conceptual document. I also consulted additional materials from the Oppenheim Foundation in Cologne, including correspondence and reports that illuminate his role in shaping policy ideas. Beyond these primary sources, my research engages with diplomatic correspondence, propaganda publications, and a broad range of secondary scholarship to contextualize Oppenheim's proposals within wider German and Ottoman strategic thinking.

AB: How difficult was it to access related Ottoman sources -- if any - on events within the empire?

SB: Some of the sources in the Ottoman Archives are restricted, and it is well known that the materials made available to the public are selectively chosen--yet they still include essential documents. The ones I was able to access online were particularly helpful for my research.

AB: What methodological approaches do you base your analysis on--historical ideas, discourse analysis, or political science?

SB: My analysis is grounded in historical methodology, particularly in the close examination of primary sources to trace how developments unfolded over time and how historical actors understood their own contexts. I situate events, ideas, and individuals within their specific historical moments to reveal the dynamics and meanings that shaped their actions, with particular attention to the evolving relationship between Assyrians and Kurds.

AB: How did Pan-Islamism and Pan-Turanism differ -- and how were the two movements combined for political purposes?

SB: Pan-Islamism emphasized the religious unity of Muslims under the Ottoman Caliphate, while Pan-Turanism promoted the ethnic and linguistic solidarity of Turkic peoples. Under Sultan Abdülhamid II, Pan-Islamism aimed to strengthen the empire through Islamic solidarity, whereas Pan-Turanism, later embraced by Young Turk intellectuals, emphasized Turkish national identity. Despite their differences, Ottoman leaders--particularly the Committee of Union and Progress--combined the two ideologies to rally Muslims against foreign powers and foster unity among Turkic groups. The Young Turks gradually shifted their focus toward Pan-Turanism, especially in response to rising Arab nationalism and separatist movements.

AB: Some Turkish scholars argue that the Jihad call wasn't targeting the non-Muslim citizens of the Ottoman Empire. But what immediate effects did the call to jihad have in the Ottoman Empire, which the German Empire was apparently urging as an ally?

SB: A very important question indeed. Some Turkish scholars indeed maintain that the Ottoman declaration of jihad during World War I was aimed exclusively at the Allied Powers. However, the wording of the declaration did not explicitly exclude the Empire's own non-Muslim subjects--such as Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks--from its scope. Officially, it was directed against the "Allied Powers and their collaborators," but in practice, the notion of "collaborators" was often interpreted in ways that aligned with pre-existing sectarian suspicions. The call to jihad was proclaimed in mosques throughout the empire, and while it served a strategic function for the Ottoman--German alliance, its local implementation frequently acquired a violent sectarian dimension. Notably, in Constantinople, shortly after the proclamation was read, an Armenian-owned hotel was attacked and destroyed--an incident that vividly illustrates how the rhetoric of jihad could translate into acts of communal violence on the ground.

AB: To what extent was the German side aware of these consequences in the Ottoman Empire?

SB: The genocide of Christian communities--particularly Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks--was orchestrated primarily by the Ottoman Young Turk leadership, but Germany, as the Empire's close wartime ally, was fully aware of what was happening. Germany's overriding priority was the maintenance of the wartime alliance and the stability of the Ottoman front, which meant that humanitarian concerns were subordinated to military and strategic interests. In that sense, although Germany did not initiate or directly administer the genocidal policies, its political silence and continued military cooperation amounted to a form of complicity by omission.

AB: To what extent does your work help to better understand the relationship between religion, nationalism, and violence in modern political discourse?

SB: The jihad declaration illustrates how religious rhetoric is mobilized to serve nationalist and political ends, transforming faith-based concepts into instruments of exclusion and violence. In the Ottoman context, the call to jihad was framed as a defense of Islam against external aggression, but it also functioned internally to consolidate the Young Turk regime's nationalist agenda. It incited segments of the Kurdish, Turkish, and other Muslim populations to attack Christian communities indiscriminately--acts that were justified not only in religious terms but also as expressions of loyalty to the Ottoman state.

AB: Were there moments when you were surprised by the results you gained yourself?

SB: When I first learned that there was an office in Berlin publishing El-Jihad magazine almost every two weeks, it drew my attention more and more. My conclusion is that religion has almost always been used as a tool by policymakers.

AB: Thank you for the interview, and I wish you success in your future studies.

or register to post a comment.