However, after the 1915 Sayfo Genocide, the names of villages and towns were Turkified, and the closure of Assyrian-language academies and schools led to the suspension of Assyrian press and publishing. In the following decades, the Assyrian language, once vibrant across the region, faced the threat of extinction, and today it is listed in UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Endangered Languages.

Zahrire d'Bahra: The first Assyrian newspaper

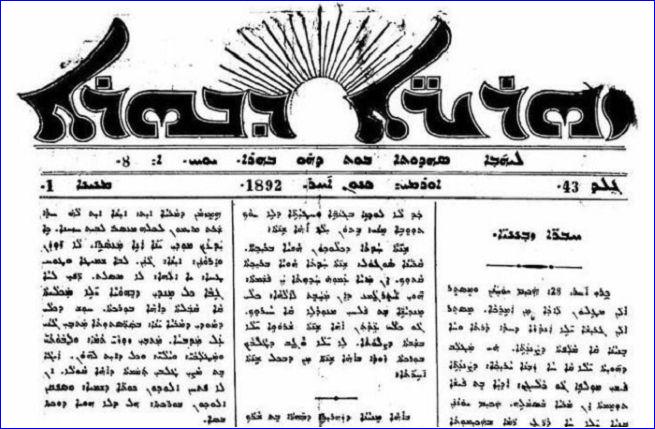

Zahrire d'Bahra, the first newspaper in the history of Assyrian journalism, was established by the American Presbyterian Mission, which had settled in the Urmia region with the aim of spreading the teachings of Jesus Christ through word and action among the Assyrian Christians. Although the mission provided the framework, the editorial management was undertaken by local Assyrian Christians.

The newspaper began publication on 1 November 1849 and continued until 1918. Its end came after the Sayfo Genocide, when the American Mission's activities were halted.

The newspaper was published in Eastern Assyrian and became one of the longest-running Assyrian newspapers in history. In addition to general news, it focused on religious, educational, social, cultural, and humanitarian topics, aligned with the Presbyterian tradition of moral education and enlightenment.

According to researcher and journalist David Vergili talking to Agos Gazete's Marta Sömek, "Zahrire d'Bahra was probably the longest-lived Assyrian newspaper. It deserves special recognition as the first of its kind. The Catholic and Protestant missions active in the region played a key role in sustaining its long lifespan. Given the literacy rates of that era, I don't think it reached mass audiences, but it remained a vital cultural bridge."

Following the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), Assyrian-language schools and educational academies were shut down. The absence of newspapers and print publications in the Assyrian language contributed to the erosion of linguistic and cultural memory.

Vergili explains "Throughout history, and particularly in the Middle East, wars, massacres, denial policies, and genocides have caused immense cultural and linguistic losses among marginalized communities. After Sayfo, the Assyrians lost their social, economic, and religious institutions--and eventually their schools. With this, printing and publishing came to a halt across many regions of the Middle East. What followed was a complete cultural and social rupture. Assyrian, which relied largely on oral transmission, weakened and came under threat of extinction."

The rebirth of hope, Gazete Sabro

In March 2012, after more than a century of silence, a new voice emerged from Tur Abdin--the historical heartland of Assyrians in southeastern Turkey. "Sabro", meaning "Hope" in Assyrian, began publishing monthly as the only newspaper in Turkey featuring Assyrian content.

With 13 pages in Turkish and three in Assyrian, Sabro was created to preserve the Assyrian language and to serve as a voice for Assyrians scattered across the diaspora. Later, a women's magazine titled "Neshe" ("Women") was also launched under the same roof, but it ceased publication in 2020 due to financial difficulties.

Vergili, who serves as the editor-in-chief of Gazete Sabro, emphasizes the paper's cultural significance: "Sabro continues to publish modestly, yet meaningfully. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the Tur Abdin region and in Assyrian heritage.

Sabro connects readers with that reality, blending political, cultural, and social developments from a Assyrian perspective. Its contribution to the Turkish media landscape lies in its multilingualism and cultural diversity. For us, the presence of Assyrian in print--when there are no educational institutions left--is deeply valuable."

Distributed through a subscription system, Sabro reaches readers both in Turkey and abroad, including cultural institutions and Assyrian associations. Its website also provides regular updates.

Vergili adds "We publish news and opinion pieces about Assyrian communities across the Middle East, Europe, Tur Abdin, and the diaspora. Thanks to the Turkish sections, Sabro can also be read by non-Assyrian speakers--both Assyrians who no longer know the language and people of other backgrounds."

"In a world where the Assyrian language faces the risk of disappearance--both in Turkey and in the diaspora--publishing in our mother tongue is an act of resistance," says Vergili. "Despite every challenge and limitation, insisting on Assyrian means safeguarding its transmission to future generations. The continuity of Sabro and other Assyrian media outlets will determine whether the language survives."

or register to post a comment.