Amir Ali Javadian)

Amir Ali Javadian)

It was the summer of 1980. Saddam Hussein began assembling an army of over 200,000 soldiers -- at the time the second largest army in the Middle East -- its ranks filled with people from all regions of Iraq, Assyrians included.

My father, Binyamin Youkhana, stood among them.

He joined the army at 18 years old, part of a mandatory service if you couldn't read. As a shepherd on his family's farm, he hadn't gone to school.

When the war broke out, my father shipped to the front lines, and the Assyrians of Iraq became pitted against their Assyrian brothers from Iran.

Iraq made progress in the early months of the war and expected a fast victory; but as Christmas neared, their advance stalled. They didn't know it at the time but they stood at the dawn of what would become one of the deadliest wars in recent centuries.

My father recalled that early in the fighting a shell fell next to him and didn't explode. Perhaps, he said, it was a sign that God lived with him through this hell on earth.

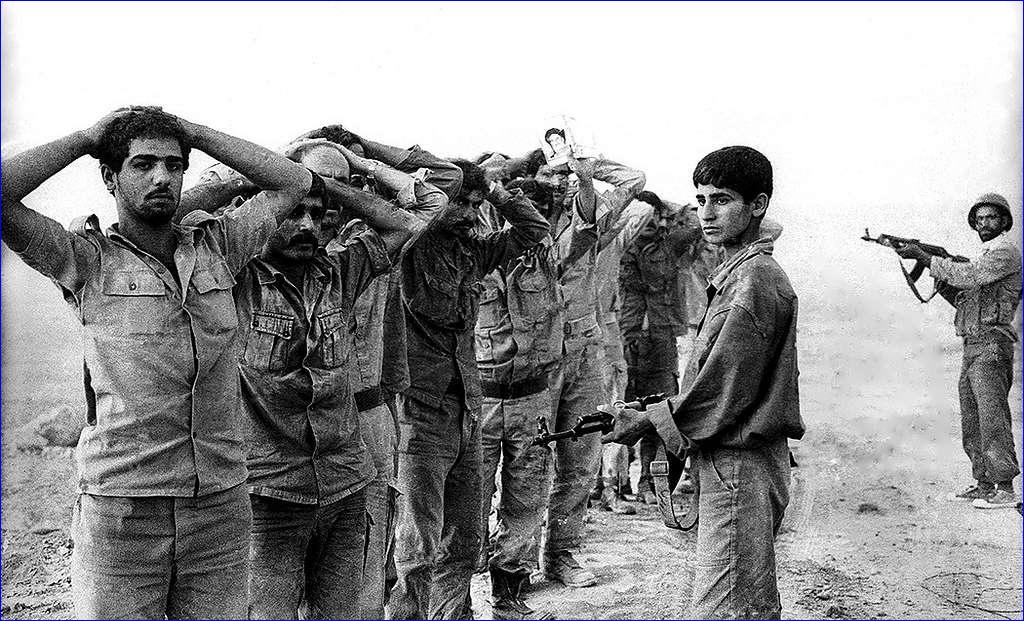

Two years into the war, Iranian forces captured my father and more than one hundred Assyrians in east Basra, shuttled them across the border to Ahvaz, then to a prison in Tehran, and finally to a prison camp in Karaj.

In prison, on top of the torture endured by the captured Iraqi soldiers, my father spoke about the discrimination Assyrians faced for their ethnicity and religion. Iranian guards pressed them to convert to Islam, he said, but they held steadfast in their faith.

To pass the time, Assyrians taught each other to read and write in Syriac. My father began learning the letters, pronouncing the vowels, writing his name, and finally reading.

But life in the prison was brutal, he said. Food and medical care was prioritized for Iranian soldiers, so the prisoners faced severe starvation and unchecked illness. Beatings became regular. Iranian guards later deployed psychological torture -- spreading false information about the war like claiming Iraq had fallen and the prisoners families killed.

Through this hardship, my father told me, Assyrians in the prison camp formed a close-knit community that steered them through these hard times. The men shared stories of their families and traditions, like teaching each other new songs to keep their spirits up. My father said the Assyrian culture breathed alive as the men held private prayers, celebrating their faith in secret to avoid more beatings.

Meanwhile, the war dragged on. Conditions in the prison camp diminished. Harsh winters added to their misery. My father described enduring freezing temperatures with little clothing and improper shelter. Hypothermia took many lives. The prisoners faced increasing health issues. The years of malnutrition, hard labor, and relentless stress had taken their toll. The small hope of eventual freedom, my father said, kept them going.

Rumors of a possible prisoner exchange began to circulate through the camp in late 1989. Outside the prison walls, the International Red Cross was negotiating with the Iraqi and Iranian governments for a mass exchange. It was a glimmer of hope after unyielding physical and psychological suffering.

In September 1990, after eight years of captivity, my father and just a few other Assyrians were released in an exchange. In total, over 70,000 prisoners from both sides returned home.

It was a moment of mixed emotions -- joy for the freedom, but sorrow for those who left behind or that had perished. My father was transported to an exchange point inside Iraq and handed over to Iraqi officials.

The journey back home felt surreal, my father said. He had grown emaciated and couldn't understand the feeling of finally being free. And though the countryside was destroyed by war, as my father approached Iraq he said it was a welcome sight and he longed to see his family, to hold them, and to assure them he was alive.

Tears and deep embraces of love greeted my father on his return home as he found his family alive. The war had left its mark on everyone in different ways, he said, but the joy of the reunion provided a temporary relief from their collective suffering.

Assyrian communities in both Iraq and Iran suffered during the war -- and they're still recovering. Many families lost loved ones, their homes and villages destroyed, and many others fled overseas, never to return to their ancestral homeland. Those that remained banded together to rebuild what was lost.

Destruction also lingered under the surface. The war left deep psychological scars as former prisoners struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Nightmares, flashbacks, and anxiety became a daily part of life, and the few avenues for mental health support amplified those challenges.

As I grew older, my father shared his stories with us, not for pity but to give a sense of history and identity. His experience is not just a string of personal memories but part of a collective history that shapes our community's identity and guides our future. My father speaks most of the importance of education -- the suffering in the camp taught him the power of knowledge, faith, and community.

And despite my father's release from the prison camp over three decades ago, many Assyrian families still live without knowledge of the fate of their loved ones who were captured during the war. A lack of consistent record keeping at the time complicates their search.

My father is one of the lucky ones. The memory of his fellow prisoners lives on through his stories. But will these families ever discover their own truth?

or register to post a comment.