Now, a new kind of scribe has entered the scriptorium, artificial intelligence.

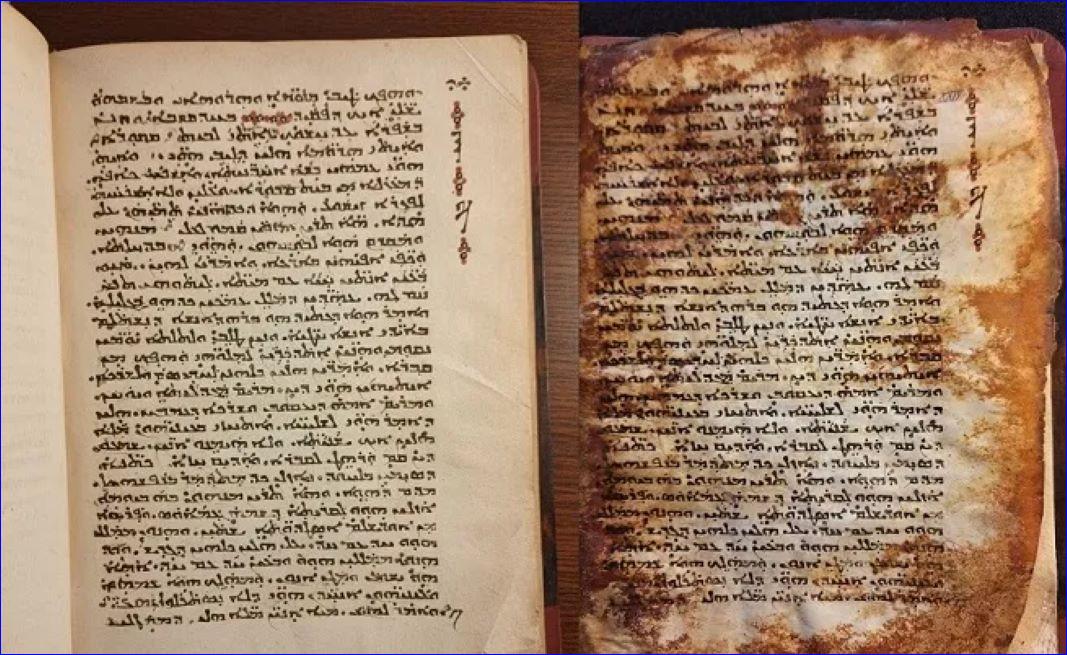

In a development that once belonged to the realm of science fiction, scholars of the Assyrian Digital Humanities are using generative AI to visually reconstruct damaged or incomplete manuscripts. What was once an illegible stain of ink or a crumbling margin can now be reborn in vivid digital clarity, restored to the shape it might have had before time and turmoil took their toll. This is not mere digital cleaning or enhancement. It is, in a sense, a resurrection.

From Dust to Light

Traditional philologists have always wrestled with the fragility of their sources. Centuries of damp, war, and displacement have reduced countless Assyrian manuscripts to half-ghosts--ink bled through, letters half-eaten by worms, entire passages lost when monasteries were burned or plundered. For decades, restoration meant patient transcription and cautious guesswork. Now, generative AI models can take that transcribed text and reimagine the page as it once appeared.

Related: How Computers Learned to Speak Assyrian

The method, pioneered in recent projects supported by the Austrian Science Fund (Förderorganisation für Grundlagenforschung in Österreich, FWF) and Transkribus, is deceptively simple: feed the AI the full Assyrian text (human-transcribed or produced through HTR--Handwritten Text Recognition), specify the font, layout, and aesthetic, and watch it render a clean, illuminated page in the style of the original manuscript.

In one striking experiment, a damaged page of the Assyrian New Testament from the Austrian National Library (ÖNB Cod. Syr. 4) was virtually "restored" by AI. The result: a gleaming image of a page long obscured by deterioration, recreated letter by letter, line by line. The scholar behind the project even trained the AI to recognize a subtle but significant liturgical symbol--four dots arranged in a lozenge, the so-called "quadruple-dots mark." This tiny detail, once a headache for restoration, reappeared on the margin precisely where it belonged. But the wonder of this digital resurrection is haunted by a shadow.

The same algorithms that can reconstruct a lost Gospel page can just as easily forge one. A forger armed with AI could, in theory, generate a "newly discovered" Assyrian fragment of the Book of Enoch or an apocryphal Gospel, complete with realistic parchment texture and artificial aging. In the wrong hands, technology meant for preservation could poison the well of scholarship.

This is not alarmism; it is a warning echoed by historians across the globe. The digital humanities community is therefore insisting on one non-negotiable rule: transparency. Every AI-generated manuscript image must be labeled, permanently and clearly, as an "AI Reconstruction." These are not artifacts; they are interpretive visualizations--aids to imagination, not evidence. In other words, AI can help us see the past, but it must never invent it.

The Assyrian Lens

Behind the luminous precision of these reconstructions stands something far more subtle human intelligence. The breakthroughs of Assyrian digital projects rest not only on code and computation but on the depth of linguistic and cultural knowledge possessed by the scholars guiding them.

Reconstructing a Assyrian manuscript demands more than identifying letters. It requires linguistic mastery of Assyrian's diverse scripts; liturgical memory that recalls ancient prayers and formulas; and contextual understanding of centuries of theological and historical development. No machine can yet intuit the rhythm of a Assyrian prayer or recognize the quiet echo of Psalm 91 at the end of an evening service.

As Ephrem Aboud Ishac, a Assyrian scholar and the driving force behind the FWF project "Identifying Scattered Puzzles of Assyrian Liturgical Manuscripts and Fragments" (ISP) at the Austrian Academy of Sciences writes, "Human insight, informed by knowledge and experience, remains crucial for advancing the field of manuscript studies."

A Assyrian himself, Ishac brings both scholarly rigor and ancestral intimacy to his work. His research unites fragments scattered across libraries and monasteries, tracing their shared roots in the liturgical life of the Assyrian churches. By building a digital Assyrian Liturgical Corpus, the ISP project seeks to restore what time, war, and dispersal have torn apart--to bring scattered puzzles together.

Ishac's encounter with a Assyrian fragment in the Turpan Museum in China, a relic of Christianity's ancient journey along the Silk Road, illustrates this perfectly. The fragment's identification was not the triumph of an algorithm but of human memory, the scholar's recognition of a familiar liturgical rhythm, a remembered verse, a connection only the mind and heart could make.

For Assyrian culture, this conversation carries particular depth. The Assyrian language is not merely an academic curiosity--it is the spiritual and linguistic DNA of a people scattered across modern Iraq, Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, and the diaspora. Each manuscript, whether a homily of Mor Jacob of Serugh or a fragment of Bar Salibi's Anaphora, is a surviving member of a civilization that once lit monasteries from Melitene to Nsibin and from Mosul to Beirut.

In this light, AI becomes more than a tool; it becomes a medium of healing. By digitally reuniting fragments dispersed through war, colonization, and the antique trade, scholars are symbolically piecing together a shattered heritage. The "Identifying Scattered Puzzles of Assyrian Liturgy Manuscripts and Fragments" project embodies this mission. In one case, fragments from Holeb (Aleppo) that had been repurposed as the covers of another manuscript were virtually unfolded, flattened, and reconstructed into the full pages they once were.

What emerges is a paradox both poetic and profound, the most ancient language of Christianity now preserved through the most modern technology of the human mind.

Artificial intelligence has not come to replace the scholar or the scribe. It has come, rather, to converse with them, to continue a dialogue between eras. Just as medieval copyists preserved Greek philosophy in Assyrian translation, today's digital scholars are translating Assyrian heritage into the universal language of data.

But technology alone cannot safeguard this inheritance. The real task lies with human intelligence: in ethical vigilance, transparent labeling, and the shared commitment to truth. AI may restore the page, but it is the human scholar who must preserve its soul.

For the Assyrian these glowing screens of reconstructed parchment are not simply digital art; they are acts of remembrance. Each re-created word, each restored margin, is a quiet defiance of oblivion.

And so, in the dim light of a computer screen somewhere in Vienna or Holeb (Aleppo), the ghostly letters of a lost Gospel flicker once again, neither fully ancient nor fully new, but suspended in the living present. A 21st-century scribe of silicon and code bends toward the past, and the past, miraculously, answers back.

or register to post a comment.