The Pope's words resound deeply for the various Syriac Christian communities across Europe, the Americas, and Australia, where generations displaced by genocide, war, and persecution face the twin challenges of assimilation and amnesia. His call is particularly relevant to the legacy of Father Boulos (Paul) Bedari, whose life work foreshadowed the very concerns the Pope now echoes. For Bedari, preserving Syriac identity--in liturgy, in language, and in communal consciousness--was not a nostalgic exercise. It was, and remains, a matter of survival.

In a moving celebration of Palm Sunday 2025, the faithful of Zakho commemorated not only the triumphal entry of Christ into Jerusalem but also the life and legacy of one of their own great sons--Father Boulos Bedari. The day began with a grand procession led by Bishop Mar Felix Saeed Dawood Al-Shabi, beginning at the Chaldean Church of Mar Gorgis and making its way to the historic village of Bedaro, now part of the growing city of Zakho. Hundreds of parishioners joined the joyful march, waving palm fronds and singing hymns. At the conclusion of the festivities, a statue was unveiled to honor Father Bedari, a towering figure in the religious, cultural, and national history of the region.

Born in 1887 in Bedaro, just two kilometers outside Zakho, Father Bedari's life was intertwined with the land and its heritage. The village's name--"Battlefield" in Syriac Aramaic--hearkens back to an ancient victory by Mar (Saint) Qardagh of Arbela over the Roman army, a symbol of resilience that would characterize Bedari's own life.

From a young age, Bedari showed a keen love for knowledge. Recognizing his potential, the parish priest selected him to study at the Seminary of Mar Yohanna Habib (St. John the Beloved) in Mosul, a prestigious institution founded by the Dominican fathers in the 19th century. Over more than a decade, he immersed himself in theology, languages, and sciences, laying the foundation for his future service.

In 1912, he was ordained a priest by Bishop Timotheus Maqdassi. Father Bedari initially served his home village, but his mission soon expanded. He ministered in Beirut, Hasakah, and Qamishli, where he directed the Kifah School, known for its high academic standards, particularly during his leadership.

Father Bidari was also a rebellious and defiant figure. In February 1960, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, a fierce Arab Nationalist, visited northeastern Syria during the brief existence of the United Arab Republic (UAR), the political union between Egypt and Syria (1958--1961). This visit was part of a broader campaign to solidify his control over Syria and promote pan-Arab nationalism. While many Arab Syrians welcomed him with enthusiasm, the various Syriac Christian communities reacted with suspicion, resentment, and even open resistance--especially in places like Qamishli, which had significant Christian populations. Many of the Syriac Christian communities in the area were survivors or descendants of survivors of Sayfo--the Ottoman-led genocide of indigenous Christian communities--and were particularly wary of pan-Islamic or exclusive nationalist ideas and Nasser's pan-Arab rhetoric emphasizing Arab identity to the exclusion of other ethnic and cultural groups. Assyrians and Syriacs feared forced Arabization, loss of linguistic and cultural rights, and marginalization of their Christian identity.

During his visit, Nasser publicly referred to the region as an "Arab land," further alienating non-Arab Syriac populations who view their identity as distinct from that of Arabs. After Nasser's speech, Father Bidari ascended the stage without permission and shouted: "O barefoot Arabs! You came to our lands as invaders. Go back to your deserts!"

Security forces arrested him immediately and dragged him to intelligence headquarters.

Nasser was unable to differentiate between the non-Arab Syriac Christians and the Coptic Orthodox in his native Egypt, who largely adhere to Arab culture. He noted to his aides his displeasure at seeing non-Arab culture and identity being displayed in Syria and made sure that clubs promoting Syriac language, literature, and Christian heritage came under pressure. One of the most prominent Christian football clubs in Syria, Rafidain Sports Club in Qamishli, deeply tied to the community's cultural and social life, was shut down. Activities perceived as promoting non-Arab identity were banned or tightly monitored, including Syriac language classes, traditional dance/music groups, and heritage preservation societies. Church-affiliated youth and cultural groups were also scrutinized, especially if they operated outside of strictly religious activities. Nasserist policies discouraged any form of ethnic or religious communalism that was not explicitly Arab-Muslim.

Father Bedari was a prolific writer and scholar. Fluent in Syriac, Arabic, French, Kurdish, Latin, and English, his works spanned languages and genres. Many of his manuscripts, including critiques of church leadership, historical poems, and geographical treatises, remain unpublished or were lost due to his many travels and the political turmoil of his time.

Throughout his ministry, Father Bedari placed special emphasis on teaching the sacred Syriac language, church hymns, and traditional liturgical practices. But more than that, he instilled in his students a deep sense of cultural pride and national unity, transcending the sectarian divides that had fragmented the Syriac-speaking peoples. Graduates of his school were known for their strong attachment to their language, faith, and ancestral heritage.

His writings reflect a passionate plea for unity among all branches of the Syriac-speaking peoples--Maronites, Assyrians (Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East, Russian Orthodox, and various Protestant Churches), Syriac Orthodox, Syriac Catholics, and Chaldean Catholics alike. During a eulogy he delivered in honor of Patriarch Ephrem Barsoum (of the Syriac Orthodox Church), during a commemorative gathering held in Qamishli, he famously declared:

"We are all, with our different names, equally Syriac--without one being superior to another. May God's curse be upon the one who scattered the Syriac people into warring factions..."

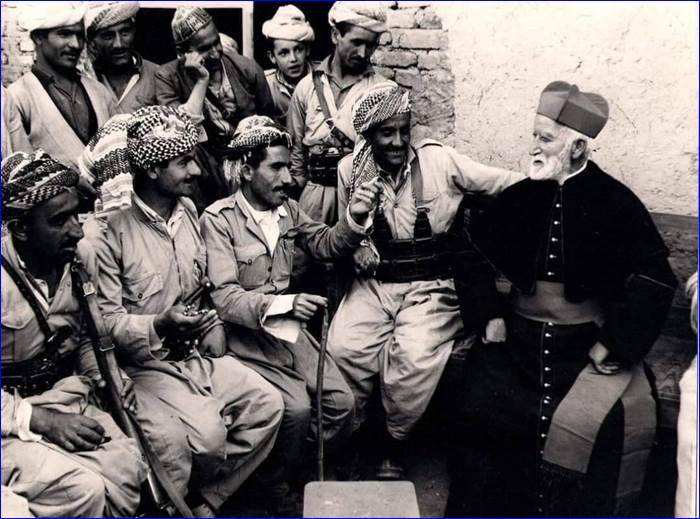

In 1960, the Chaldean Patriarch Paul Cheikho summoned Father Bedari back to Iraq, where he joined the Supreme Council of the Kurdish Revolution under Mulla Mustafa Barzani. He fought and advocated tirelessly in the mountains of northern Iraq, the land he loved so dearly and tried to get Barzani's approval for a Syriac Christian/Assyrian national homeland in northern Iraq. But when Barzani grew in power, he reneged on his promises and Fr. Bedari's efforts were in vain. His dream was not merely political--it was a call for a national homeland for his people, the original inhabitants of these ancient lands. Father Bedari's revolutionary engagement distinguished him even among his contemporaries. He stood out as one of the rare Chaldean Catholic figures who openly sought self-determination for his people, contrasting with the more cautious stance of others.

Father Bedari never parted from two things: his prayer rosary and his pistol -- symbolizing his dual commitment to faith and defense of his people. His pistol remains preserved today in the Chaldean parish of Jesus the King in Hasakah.

He spent his final years in the Monastery of Mar Gorgis near Mosul, passing away in 1974 at the age of 87. He was laid to rest in the Cathedral of the Martyr Masqenta in Mosul, remembered by all who knew him as a fierce fighter for his faith, his people, and their rightful place in history. The story of Father Paul Bedari is one of faith, courage, scholarship, and undying devotion to a people and a cause greater than himself. His life continues to inspire new generations to cherish their identity, heritage, and the bonds that unite them.

Pope Leo XIV lamented that "the priceless heritage of the Eastern Churches is being lost" as younger generations in the West grow increasingly detached from their ancestral traditions. He noted that many of these communities, particularly those born into the diaspora, face a quiet erosion of their identity. In his words: "It is vital, then, that you preserve your traditions without attenuating them, for the sake perhaps of practicality or convenience, lest they be corrupted by the mentality of consumerism and utilitarianism."

Father Bedari would have recognized this danger. As a scholar, militant cleric, and cultural visionary, he understood that identity could not survive on sentiment alone. It required intentional formation--schools to teach Syriac, churches to uphold Eastern liturgical life, and a communal narrative capable of bridging ancient roots with modern realities. Whether resisting Arabization in Qamishli or petitioning Kurdish leaders for Christian autonomy in Iraq's highlands, Bedari fought not just for physical safety, but for cultural and spiritual continuity.

It is precisely this continuity that Pope Leo XIV now seeks to uphold, calling on Latin bishops and global Church structures to "concretely support Eastern Catholics in the diaspora in their efforts to preserve their living traditions." His directive is a challenge to complacency--not just in Rome, but in the parishes and dioceses of the West that host dispersed communities. In Pope Leo's vision, these communities are not relics of a lost world but vessels of renewal for the broader Church. "The contribution that the Christian East can offer us today is immense," he said, praising the mystagogy, liturgical richness, and penitential spirituality that remain alive in Eastern worship. These, he noted, are "medicinal" traditions--a term that could easily describe the example of Father Bedari himself, whose rosary and pistol embodied the paradox of faith and defense, devotion and resistance.

In modern times, amid trends of secularization and modernization, Syriac Christian identity has expanded to include pre-Christian heritage under Assyrian, Aramean, Syriac, or Chaldean labels. These labels, which largely follow ecclesiastical divisions, are often a source of further division within the community and often reflect the unique identities of each sect and that sect's regional ties and identity. Syriac Christian identity today is a layered one: rooted in religion, shaped by history, and negotiated through competing narratives of unity and distinction.

For Syriac Christians living in the diaspora, the story of Father Bedari is more than a chapter of distant history; it is a living call to remember who they are and the importance of unity. In lands far from Zakho and Mosul, where assimilation and forgetfulness threaten to erode ancient traditions, Bedari's life stands as a witness to the sacred duty of preserving faith, language, and communal memory. His fierce love for his people--their prayers, their hymns, their identity--reminds those scattered across the world that exile need not mean erasure. Wherever they live, Syriac Christians are called to cherish and renew the spiritual and cultural inheritance that was passed down at great cost, lest it be lost to the tides of time. For the diaspora, Pope Leo's message is both a reassurance and a responsibility. They are, as he put it, "lights in our world," called not merely to adapt but to illuminate. They must carry forth the legacy of saints and fathers like Boulos Bedari--men who refused to compromise the sacred even under persecution. As Pope Leo concluded, "Christ's peace is not the sepulchral silence that reigns after conflict... but a gift that brings new life." That peace must be built not only by diplomats and statesmen, but by families, parishes, and pastors who pass on the prayers, songs, and stories that shaped our ancestors. In this, the life of Father Boulos Bedari is no historical footnote. It is a map. And now, thanks to voices like Pope Leo XIV, the Church universal is being summoned to follow it.

or register to post a comment.