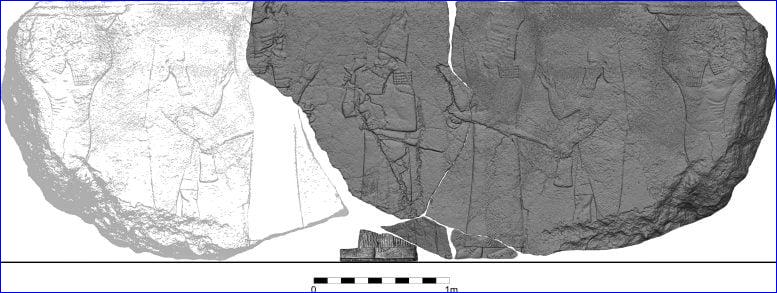

The relief shows the seventh-century BC ruler of the Assyrian empire alongside two prominent deities and other figures. It was carved into a massive stone slab measuring 5.5 meters in length, three meters in height, and weighing around 12 tons. The discovery stands out not only because of its size, but also because of the unique scenes it portrays.

"Among the many relief images of Assyrian palaces we know of, there are no depictions of major deities," says Prof. Dr Aaron Schmitt, head of the excavations in the North Palace and a member of the Institute of Prehistory, Protohistory and Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology.

Historical significance of Nineveh

The ancient city of Nineveh, located near the modern Iraqi city of Mosul, is considered one of the most important urban centers of northern Mesopotamia. Under King Sennacherib, it became the capital of the Assyrian empire in the late eighth century BC. Since 2022, Aaron Schmitt and his team have been excavating the Kuyunjik mound, which lies in the central area of the North Palace built by King Ashurbanipal.

These excavations are part of the Heidelberg Nineveh Project, launched in 2018 under the leadership of Prof. Dr Stefan Maul from the Department of Languages and Cultures of the Near East at Heidelberg University. In the late 19th century, British archaeologists were the first to explore the North Palace and uncovered large-scale reliefs that are now displayed in the British Museum in London.

Religious iconography and symbolism

At the center of the newly discovered relief is King Ashurbanipal, the last great ruler of the Assyrian empire. He is flanked by two supreme deities: the god Ashur and the goddess Ishtar, who is the patron deity of Nineveh. Following them is a fish genius, a figure believed to grant salvation and life to both the gods and the king. Another figure with raised arms appears behind them and will likely be identified as a scorpion-man during restoration.

"These figures suggest that a massive winged sun disk was originally mounted above the relief," explains Aaron Schmitt. In the coming months, the research team will analyze the depiction and its archaeological context in detail using data collected on site, with plans to publish their findings in a scientific journal.

According to Prof. Schmitt, the relief was originally located in a niche across from the main entrance to the throne room, i.e., the most important place in the palace. The Heidelberg researchers discovered the relief fragments in an earth-filled pit behind this niche. It was probably dug in the Hellenistic period in the third or second century before Christ.

"The fact that these fragments were buried is surely one reason why the British archaeologists never found them over a hundred years ago," assumes Prof. Schmitt. As agreed with the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH), the medium-term plan is to place the relief on its original site and open it to the public.

or register to post a comment.