Alamy)

Alamy)

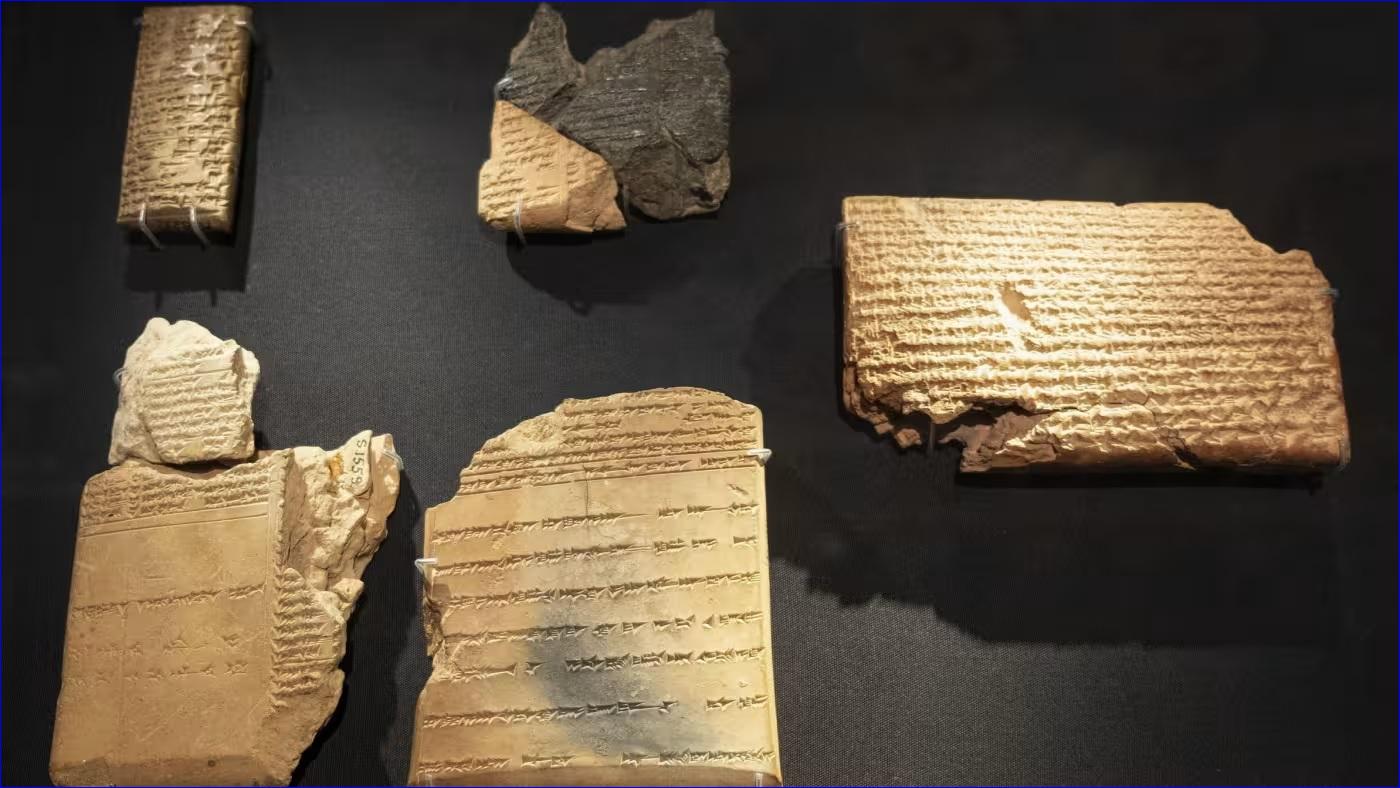

The library of Ashurbanipal is now stored in the British Museum (hence its marvellous survey in 2018), but it has taken almost 180 years for its secrets to be revealed through painstaking scholarship. Wisnom's book recounts the labours of the excavators who uncovered more than 30,000 clay tablets and fragments in the mound of earth that covered the ancient city of Nineveh (not far from the city of Mosul in modern day Iraq) and its magnificent royal palace. Austen Henry Layard (later known as "the Lion of Nineveh") led the digs, but it was his less celebrated colleague Hormuzd Rassam who made the most important discoveries. Wisnom also gives attention to the linguistic experts who deciphered the cuneiform script and the Akkadian language that the tablets were written in. It was their work that made it possible to understand in detail the mental world of this ancient ruler.

Given the great antiquity of Ashurbanipal's library, we know an extraordinary amount about it, not just of its contents, but the way in which it was managed, in part thanks to many letters that were also uncovered from the ruins of Nineveh. We know, for example, that it was formed from the libraries of his immediate ancestors, Sargon II, Sennacherib and Esarhaddon, but that Ashurbanipal was the first of his dynasty to have a real scholarly interest in its contents. He actively sought to add new texts, and even wrote material to add to the library's riches himself.

The books -- clay tablets -- were kept in Temple libraries, especially those dedicated to Nabu, the god of scribes, and the custodians of these collections were temple priests. The library was essentially the personal resource of the King and his closest advisers, all of them men. No women had access.

This librarian wanted to know much more about the organisation of knowledge in Ashurbanipal's library, as there is a fair amount of evidence, but Wisnom does not attempt a reconstruction. Her strength lies in taking a walk along the shelves of the library and discovering what the books tell us about the ideas circulating in the court of Nineveh. Prediction of the future featured heavily: astrology, medicine and divination, trying to make sense of an unpredictable world and to impose some kind of control over it.

We learn that the Mesopotamian civilisations kept data on celestial movements for more than 600 years. All this careful observation and information gathering was there to help the astrologers advise the King. So too with healthcare: the library's extensive collection on the subject, now known as the Nineveh Medical Compendium, has been made available online by the British Museum. This Mesopotamian link between personal health and the prediction of the future has now come full circle. Anyone who tracks their biometric data via a wearable device to help predict their future health is following a millennia-long tradition.

There were large sections devoted to lamentation, as a way of expressing emotions regarding the profound events that affected their lives -- death, conflict and natural disaster. There is also a sizeable section on literature. Perhaps the most famous literary work to survive from ancient Mesopotamia is the Epic of Gilgamesh, a story that survives today because of the copies discovered in Ashurbanipal's library. Other fragments of the story would appear in other excavations, but in Nineveh were found the most important copies and the best preserved.

Ashurbanipal inherited the core of the collection, but he was assiduous in adding to it, in part through seizures from the libraries of his great enemy, the Babylonians. He understood the connection between knowledge and power: he built his library to make himself more powerful, and by taking texts from his enemies, he made them weaker. Ashurbanipal's library is a useful reminder that authoritarian rule has always meant controlling knowledge, whether by seizing clay tablets or deleting websites.

The Library of Ancient Wisdom: Mesopotamia and the Making of History by Selena Wisnom, Allen Lane £30/University of Chicago Press $30, 448 pages.

Richard Ovenden is Bodley's librarian and author of 'Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge Under Attack' (John Murray).

or register to post a comment.