"My family escaped with little more than their clothes of Mardin (Turkey, nowadays) to Damascus (Syria) in 1909 fleeing from some kind of massacre. Many years later, in 1953, they emigrated to Argentina", explains the Argentine sociologist of Assyrian-Lebanese origin Ricardo George Ibrahim, 55 years old. The Turkish city that he mentions was at the beginning of the 20th century the heart of two prosperous communities of Armenian Catholics and Syriac-Orthodox with Assyrian ethnicity. Almost all of the 50,000 inhabitants in which its total population was estimated before the Ottoman genocide of 1915 were Christians.

Related: The Assyrian Genocide

The bulk of the 15,000 Assyrians who remain today in modern Turkey live precisely in the city of Ricardo's ancestors, Mardin, and in some mountains located in its surroundings known as Tur Abdin, where Turoyo is still spoken. These Christians constitute in themselves a kind of anthropological relic. They are the descendants of those who survived, not only the so-called Year of the Sword or Seyfo (1915) but all the massacres, persecutions and conflicts that occurred before and after the genocide that Joe Biden has just recognized.

Biden has made a mistake by referring to it as exclusively "Armenian." In doing so, he has overlooked that both Assyrians and Pontic Greeks alike lost between one and a half million and two million of their own. The mistake has been repeated among Latvian politicians who followed the Biden steps a few days ago. The lack of terminological precision is in no way due to the bad faith of the Armenians. The main difference of these with the rest of the peoples who suffered the same fate is that they have their own state, are better organized in the diaspora, and have influential lobbies to denounce the facts and fight for the restoration of historical memory. "We know that Assyrians and Greeks died together with our ancestors and we consider them our brothers," Aderdis R. P. assures in this regard. "It would be good to call it Armenian-Greek-Assyrian genocide or simply, the genocide of the Anatolian Christians." Indeed, the Ottomans did not establish differences between one and the other.

In similar circumstances, often part of the same death caravans, all Christians -- and not exclusively Armenians -- were deported under horrifying conditions according to an extermination plan devised by the Committee on Union and Progress and executed in 1915 by auxiliary troops of some Kurdish tribes whom the Turks duped with promises to hand over the properties of dispossessed and annihilated Christians.

In all fairness, it must be said that there were also Muslims who refused to comply with the orders, in addition to some documented cases of Kurds who tried to protect or concealed their neighbors. One of the most notable is that of Mihemede Miste, a tribal leader of the Reshkota Kurds who opposed the orders of the Ottoman governor of Diyarbakir. His home was burned and destroyed to the ground and he and his family were sentenced to exile. Armenians do not forget these gestures and recently honored his memory by visiting the grave of this kind of "August Landmesser" from Anatolia.

When the conflict ended, practically all the Christians in Anatolia had been killed or deported, which can only be explained if it is taken for granted that the triumvirate that ruled Turkey joined the Great War intending to murder with impunity all the Christians under the umbrella of their national interests and a full-fledged jihad. More than a century after those events, Ankara and a good part of the ultra-nationalist Turkish civil society remain locked in the most closed denial. Despite the overwhelming documentary evidence of that crime against humanity, they abound in the idea that they fought the Christians as an internal enemy whom they accused of fraternizing with tsarist Russia and its allies. In favor of the Assyrian-Armenian theses, it must be remembered that long before the Ottomans entered the war on the side of the Germans and Austro-Hungarians, the Young Turks had already expressed their desire to Turkify the territory to uproot its "foreign elements." Furthermore, most of the victims of this "holocaust" were brutally murdered outside the war zone and not in the heat of battle or fighting fair and square.

The caravans of death

Hundreds of documents prove that the extermination strategy employed by the Turks meets all the requirements that international law requires to classify crimes against a people as pure genocide.

They began by separating the Christians who served in the Army from the rest of the soldiers. Some were sent to labor battalions, where they lost their lives from starvation or disease. Others were directly killed. They were forced to walk on isolated roads where they were ambushed by Kurdish irregulars who had been tasked with killing them. Thousands of people ended up that way. Immediately afterward, the government prohibited them from possessing weapons and selectively assassinated their leaders and intellectuals.

Unarmed and without their best men, it was time to visit the villages and destroy their humble villagers. From the outset, they put an end to the lives of not a few men of fighting age. Later, children, old men, and women were rounded up and deported. The marches they undertook ended up turned into caravans of death: on the way to exile and concentration camps, tens of thousands more died from disease or hunger, when not machine-gunned by Kurds and Ottomans. If the Armenians threatened national unity, the Assyrians challenged their desire to build a nation without ethnic or religious fissures. The answer to the political aspirations of the Christians as a whole, much weaker and less generalized in the case of the Assyrians than in the case of the Armenians, was a sinister policy of extermination that reaped notable triumphs.

The Christian way of the cross did not end after the end of the war and the subsequent collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The coming to power of the also ultra-nationalist Mustafa Kemal was accompanied in 1919 by a new wave of crimes. Once again, they were acting in the name of the purity of a race that truly existed only in the minds of the Panturianists. Under Ataturk's orders, new purges were carried out in 1924. The final blow for the Assyrians was the signing of the Treaty of Losana, which not only deprived them of the piece of Mesopotamia that they hoped to obtain from the League of Nations but left them at the mercy of their executioners: the few who had not been eliminated. or forced into exile during the Year of the Sword and those that followed were forced to live postwar among their assassins. Officially, the Republic was going to turn them into Turkic-Semites, just as the Kurds were about to turn into Turks of the mountains.

The final icing on this fateful story of martyrdom was the war that broke out in the early 1990s between the PKK and the Ankara army. Many of those who resisted leaving for the West despite the preceding adversities, fell dejected in the crossfire during those years of violence (in this there was no distinction of creed) or were pushed to live poorly in the slums of the big cities, commonly known as "gecekondus". If the Kurds, directly involved in the conflict, paid a heavy price for this insurrection, the Christians were not left out.

Ferran Barber)

Ferran Barber)

There is something unquestionable. The Pontic Greeks of western Turkey, the Assyrians of Mesopotamia, and the Armenians of Van were once the original settlers of the regions that today are usually designated with names such as Turkey, Iraq, or Kurdistan. . And that is their main regret. They have become guests of their motherland. The latest setback for these Eastern Christians has been the loss of Arsaj by the Armenians, after an asymmetric war against Azerbaijan in which Turkish drones played a fundamental role. This same week, several deputies and senators gathered in front of the Spanish Congress to demand the release of the Armenian prisoners of war that Azerbaijan still holds.

On the other hand, the massacres did not begin or end in 1915. Practically, since the irruption of Islam in these lands, mass murders of the Christian population have been taking place periodically. Twenty years before Seyfo, the so-called Hamidian massacres also took place. It is estimated that between 200,000 and 300,000 Christians died between 1894 and 1896. Among them, there were also Assyrians. The name "Hamidian" was given in attention to the sultan of infamous memory Abdul Hamid II, who in his attempt to maintain the territorial integrity of the empire adopted pan-Islam as a state ideology. In the opinion of the representatives of the Kurdish progressive party of Turkey HDP, both the genocide of a little more than a century ago, the modern resurrection of Turkish expansionism, and the recently festering tone of nationalism prevalent in the civil society of that country drink in the same tainted intellectual sources. Until recently, there were streets in Cyprus named after some intellectual architects of the genocide such as Talaat Pasha, which in the opinion of Armenians and Assyrians, is as if the Germans had avenues dedicated to Goebbels or Himmler.

For the Kurdish leftists in Turkey that today faces an attempt to outlaw its party, Erdogan's modern pantyhose is just a manifestation of the same intellectual ferment that raised and sustained Ataturk, in the same way as Daesh or Islamic State. Erdogan is a proud heir of many of the eastern rulers who in the preceding centuries filled the gutters with the Assyrian, Armenian, Aramaic, or Maronite dead. Some minorities such as the Yazidi have suffered even worse treatment throughout history since they do not have the status of dhimmi or protected by Sharia, reserved only for the faithful of the religions of the Book.

New life in Latin America

All that chain of massacres that culminated in the genocide, as well as the distrust that dominated the relations between Muslims and Christians in all the Ottoman vilayet constituted the social climate in the midst of which thousands of Syrian, Levantine and Mesopotamian Christians decided to leave everything behind and lay the foundations for a new life in Spanish and Portuguese America. Many of them were simply tired of the segregation and marginalization they suffered as subjects of the Divine Gate. There were, therefore, not one but many migratory waves and different geographical flows.

These Eastern Christian peoples who speak Spanish today were essentially united by their oppressed condition and their religion, but they were separated by languages, ethnic origins, and cultures. How did they end up in the Southern Cone? "Often, many stopped on their way to their final destination in Marseille and did not even know where they were going," explains the Assyrian-Argentine sociologist Ricardo George Ibrahim. "According to the shipping company, they ended up landing in Brazil, New York, Boston, or Argentina, which was a booming country at the time and one of the preferred destinations for all migratory movements. There were even cases of people who were left in Senegal, telling them that they had reached America. That explains the presence of a Lebanese colony in Africa. "

Currently, Ricardo lives in Quilmes, province of Buenos Aires, where he works as a teacher. Years ago -- from 2002 to 2016 -- he also lived in Madrid. During that Spanish period, the Argentinian of Assyrian origin visited Mardin and Damascus with the hope of rediscovering his roots and traveling through the places that his ancestors once trampled on. Like so many other Argentines, Uruguayans, Peruvians, and Chileans, the sociologist has invested a good part of his life in unraveling his true identity, often blurred by the passage of time and by the cataclysms of memory that all those Christian peoples have suffered. Orientals who finally found refuge in Latin America.

False Turks and Pseudo-Arabs

They came by the thousands from Palestine, Libya, Lebanon, Iraq, and even Russia, and in countries like Argentina, they were known as Turks or, also, as Arabs. They were often co-opted by Arab and Syrian nationalists and ended up confusing their own identity with that of the nations that oppressed them. "I even know some cases of Eastern Christians from Argentina who did not suffer the genocide because they lived in Istanbul and who somehow identify with Turkey," says Ricardo George. Or put another way, some survivors of the genocide have ended up adopting the identity of their executioners and have been seduced by the siren songs of some Eastern embassies. This is especially common among Syrian Christians -- a motley mix of members of different sects.

On other occasions, these emigrants to Latin America lived in a tangle of identity confusion because, in the case of the Mardideans, for example, they came from a Turkish city, spoke an Arabic dialect mixed with Syriac, and were Christians of Armenian or Assyrian ethnicity. It was just as common for Mardin's Armenian Catholics to be looked at by their Gregorian brethren. "These Eastern Christians often took with them some of their prejudices, as well as a certain conservatism and a strongly patriarchal and authoritarian culture," Ibrahim tells us.

Many of the new generations do not even know who their ancestors were and in the midst of that nebula, they designate themselves according to the name of the Church of their great-grandparents, which used to be the center of their social life and the element of cohesion that has managed to maintain them more or less agglutinated. The Syriac-Orthodox, for example, continue to maintain certain living communities in Argentina, although their community spirit is much less consistent than that of their Armenian brothers. Unlike the latter, they never had their own schools or powerful cultural centers.

Brutal Creole racism

The beginnings of those who managed to flee to Latin America was not easy and their admission to some Ibero-American nations does not invalidate the fact that they had to face the racism of white Creole elites of European origin. In this regard, the researcher Heitor de Andrade Carvalho Loureiro has documented in a study the case of a British attempt to transfer hundreds of Assyrian families from Iraqi Mesopotamia to the Paraná jungle during the 1930s. These Chaldeans had been in a very difficult situation after the independence of the country because they had previously served the interests of the British (Levis unit), who left them later to their fate, like the League of Nations. They were not granted the promised status of their own and were exposed to the wrath of Muslims who viewed them as traitors, leading to the Simele massacre (1934).

Some of those killed in Iraq were survivors of the genocide. They had ended up in Mesopotamia after fleeing the city of Hakari through Persia, where they were also massacred in the French mission of Urmia. Many saved their lives in Turkey but were ultimately slaughtered by the Arabs. It was under these circumstances that a British society set out to bring five hundred Assyrian families to the state of Paraná. The project failed due, among other things, to the racist prejudices of the Brazilian authorities at the time that considered these "Assyrian Christians" as the lowest in the emigrant ladder.

Influenced by the eugenic policies of Europeans, they even referred to them as "parasitic." On the contrary, they were betting on importing Europeans, especially people from the Germanic environment, Portuguese and Spanish, on the condition that they were not anarchists or subversive leftists. The emigrants who did manage to reach the lands of Argentina or Brazil suffered from the same kind of aberrant prejudices. "Really, all those racist ideas were terrific," says sociologist Ricardo George Ibrahim. "Also in Argentina, the so-called Arab or Levantine was despised a lot, saying that they were not appropriate for agriculture or that they were vagabonds. And indeed, at first, they were peddlers who were selling from door to door, but they rose socially very quickly and had a very positive influence in marginalized areas where other immigrants did not go".

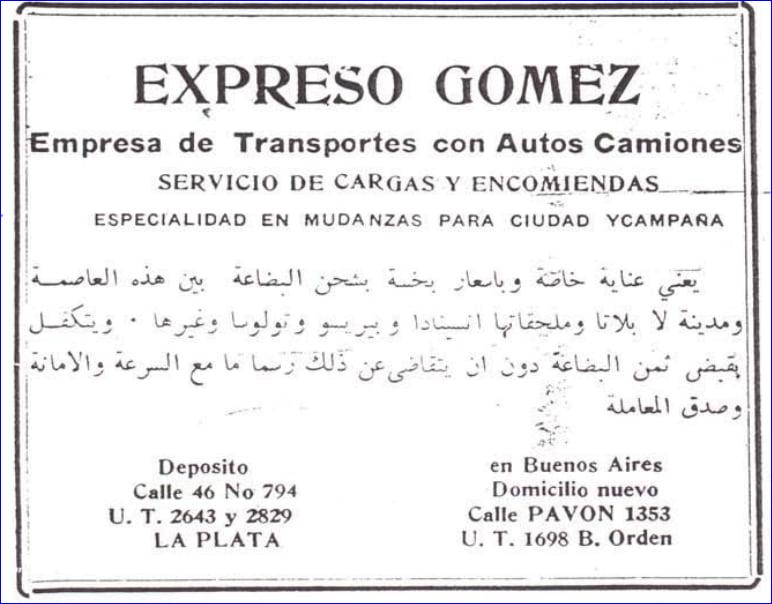

Despite everything, many Mardinenses settled in Argentina, especially in Quilmes and La Plata. A group of Assyrians even came from Russia, originally from the Iranian city of Urmia to working on the railroad and settled in Tucumán. But above all, many Syrian, Palestinian, Lebanese and Armenian Christians came. The latter were much better organized and had more of their resources because they were also more numerous. " Ricardo has spent years interviewing and studying these descendants of the survivors of the various genocides and massacres. "I know from my grandmother's older brother that many worked in refrigerators. They did not speak a word of the language, of course. A lot of people shared rooms and lived in crowded conditions in a very precarious way. There was also a branch that found employment in the brewery. from Quilmes, which explains why they settled there. When they settled, many dedicated themselves to textiles and made much progress. " These Assyrians from Mesopotamia often ended up confused with the Lebanese, Syrian and Lebanese Christians, or with the Armenians, whose emigration to Latin America was massive.

It is estimated that around 80,000 Armenian descendants currently live in Argentina alone. They arrived in the country in three main waves: before the First World War, during the genocide, and in the following years, and after the dismemberment of the Soviet Union. During the last decades, there have also been small migratory flows of Assyrians from Mardin to other countries such as Chile. Many of the members of the small Armenian community that today live in Spain have recently traveled to our country from Latin America, fleeing the difficult economic conditions facing that continent. Among the great-grandchildren of the survivors of the Year of the Sword who reside in our country there are some prominent names such as the Assyrian Efrem Yildiz, vice-rector of International Relations at the University of Salamanca, or the actor and former Armenian boxer Hovik Keuchkerian.

On the other hand, not only Eastern Christians emigrated to Latin America. Thousands of Muslims from Lebanon and Syria also chose Argentina or Brazil as their host country. But that's another story. One of the most visible manifestations of this cultural exchange between Latin America and the East is the popularity of "mate" in Lebanon and especially in Syria, one of the largest consumers of yerba on the planet.

"It has been demonstrated it was the so-called Druze swallow emigrants who took the custom of mate back to the Middle East. They emigrated en masse to Argentina to work as day laborers, but since they did not manage to gain ownership of the land, they returned to their countries of origin and familiarized their consumption ", concludes Ricardo George Ibrahim.

Ferran Barber is a journalist specialized in minorities in the Middle East, and author of the book 'In search of the last Christians in Iraq and Iran', Editorial Barrabés.

or register to post a comment.