(AINA) -- Three years ago, when I began carving the Endangered Alphabets, I discovered that even though the world has between 6,000 and 7,000 languages, those languages are written in fewer than a hundred scripts -- alphabets or other writing systems based on syllables or consonants. What's more, at least a third of those writing systems are in danger of extinction.

(AINA) -- Three years ago, when I began carving the Endangered Alphabets, I discovered that even though the world has between 6,000 and 7,000 languages, those languages are written in fewer than a hundred scripts -- alphabets or other writing systems based on syllables or consonants. What's more, at least a third of those writing systems are in danger of extinction.

Some are dying because they are used by an oppressed political minority. Some are dying because it's simply more convenient to use the global writing systems -- such as the Latin alphabet, Chinese, Cyrillic, Arabic and a handful of others -- than to carry on using a script for which there are no computer keyboards or fonts. And some are dying because the people who use them have been forced to flee their homelands.

Assyrians know this all too well -- and they know what happens when a diaspora, or forced dispersal, takes place. Even if they join an existing community in a new host nation, they are now forced to use two languages rather than one, and in the case of Assyrian (and Mandaic, and Cherokee) they may even have to use two entirely different writing systems rather than one.

Time makes the situation even more perilous. The next generation is primarily educated in the host language. Even in the new experimental total -- immersion Cherokee schools, where children speak Cherokee all day and read and write the Cherokee syllabary invented nearly 200 years ago by Sequoyah, the state requires them to take standardized tests in English using the Latin alphabet.

What's more, the young are especially drawn to popular culture, and popular culture -- television, radio, the Internet -- is dominated by the major world languages and the major world writing systems. While I was in Bangladesh recently searching for people who can still read and write the indigenous ethnic scripts of the Mro and the Chakma people, I spent some time studying Bangladesh television channels. Even though the TV offered nearly 100 channels, only 24 of those had audio in a language other than English. Even the Bengali channels often featured text in Latin letters and numbers. Only two channels were through and through Bengali, and none at all were in Mro or Chakma. TV is no friend to indigenous language and culture.

The Internet may be even worse. Even though individual scholars, translators, graphic designers and code writers are creating Unicode computer fonts for minority writing systems, including Syriac (modern Assyrian), at the same time Facebook is having exactly the opposite effect. The traditional Balinese script, for example, is endangered, but I discovered it was easy enough to find Balinese on Facebook -- where they write using the Latin alphabet. Even my Mro contacts in Bangladesh were on Facebook. In a decade it's possible that the only alphabets left in general use in the world may be those accepted by Facebook.

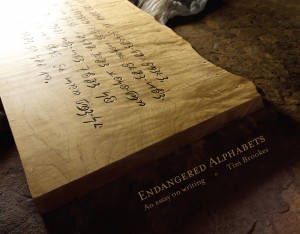

My hope is that my Endangered Alphabets Project will at least draw attention to this issue, and may even do something slightly more. I would like to create a number of carvings based on traditional handwriting in endangered scripts such as Syriac.

As things stand, I have a good friend, Dr. Charles Haberl of Rutgers University, who can translate into modern Assyrian and convert the text into the Unicode computer font, and I have carved a couple of pieces using his help in this way.

But I would prefer something written by hand. Handwriting is an extraordinary and under-appreciated skill: it combines in equal measure the need for universality and clarity, so all can understand it, with the opportunity for individual self-expression, so we can recognize the person who wrote what we read.

What I would really like to do, then, is to be in contact with someone who can write something for me -- perhaps a short poem, perhaps a proverb, something that deeply expresses Assyrian culture and tradition -- by hand, so what I carve is a replica of the actual movement of a human hand, with its own expression of that hand's owner and his or her mind.

In a way, that is what writing offers, and has always offered the chance for one person to withstand time. My aim is to add another layer; by carving the Endangered Alphabets, I'm also hoping to enable one culture to withstand time, no matter how few its numbers, or how far from home.

Editor's note: Any Assyrian wishing to contribute to Tim's project may contact Tim at brookes@champlain.edu

or register to post a comment.