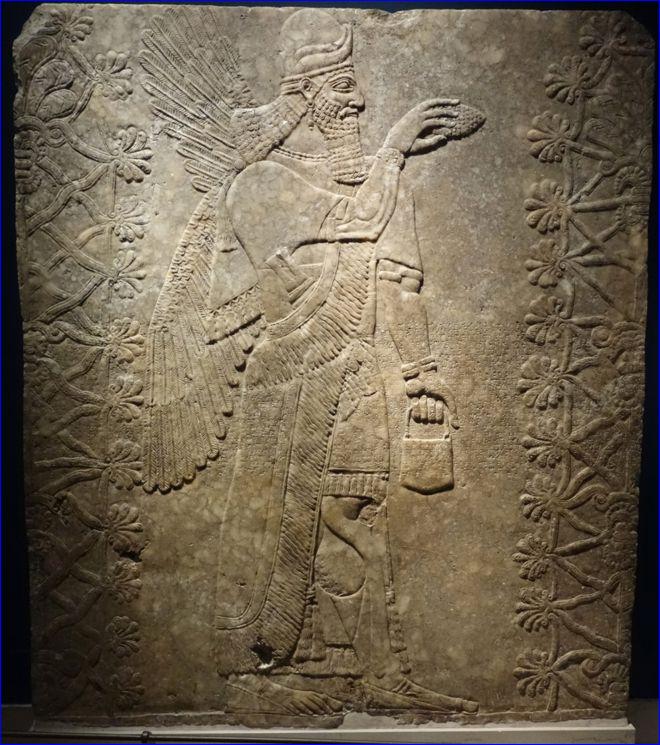

The genie is a powerfully built man, with wings sprouting from his back. About 2m high, it is carved in relief on a stone panel, holding a pine cone, and facing a pattern that represents the tree of life. The genie symbolised both protection and fertility - its role was to safeguard and replenish the ancient kingdom of Assyria.

It was a design particularly popular with the Assyrian king, Ashurnasirpal II, who came to the throne in 883 BC, and made Nimrud his new capital.

"Ashurnasirpal and his artists were really the first to decorate many of the rooms in the public spaces within the palace," says archaeologist Augusta McMahon, lecturer at the University of Cambridge.

"One of the key symbols that appeared over and over was this genie or protective spirit. Because in the minds of the ancient Assyrians it's an enormously powerful motif, it can't hurt to have a further fertility symbol somewhere in the room."

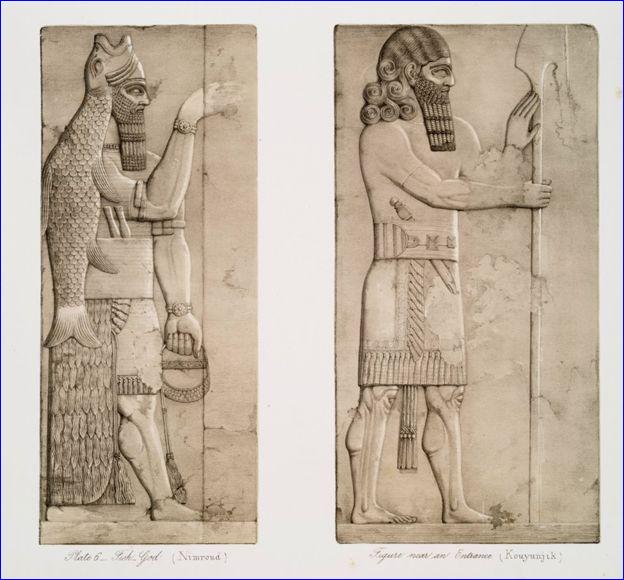

Protective genies came in all sorts of shapes and sizes. The photograph above is very similar but not identical to the one now in the hands of British police. Others had the bodies of men but the heads of ferocious-looking birds and a feathered hairstyle, still others were a combination of man and fish.

Brooklyn Museum)

Brooklyn Museum)

Our particular genie had copious amounts of curly hair and a long beard. "The really big crazy-looking hair and the massive beard were part of making him really stand out," says McMahon, who also draws attention to the "little fringed outfit that shows off these incredibly muscular legs".

The impact of all the genies side by side in the palace would have been to convey the strength and virility of the Assyrian empire.

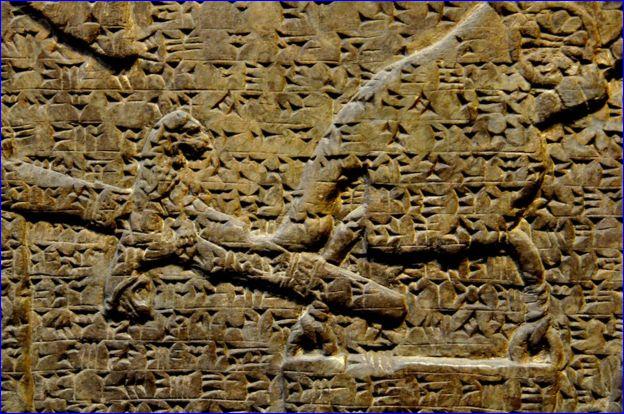

Across the belly of the genie was a smattering of cuneiform in the now extinct language, Akkadian. The text is what's known as Ashurnasirpal's "standard inscription". It lays out in minute detail his many kingly accomplishments - from treading on the necks of foes to being "king of the universe" - and was carved on many of the reliefs and sculptures that filled the halls of his palace at Nimrud.

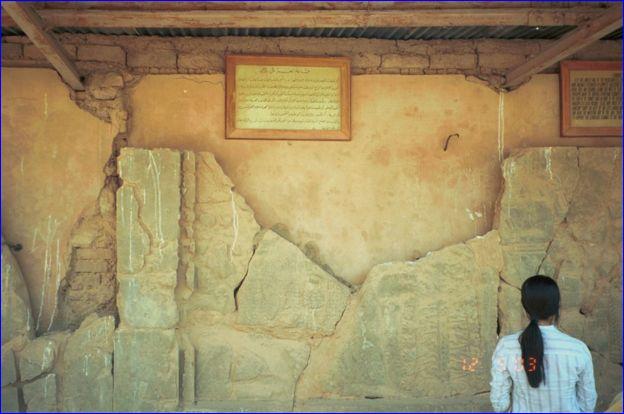

"It's my favourite ancient archaeological site," says Mark Altaweel, an Iraqi-American archaeologist whose ancestors come from Mosul - not far from Nimrud.

NYPL)

NYPL)

"You did see the reliefs in place, you can see the rooms. Even the ancient floors were sort of wobbly, and in some ways that gave it the ancient feel. You got a sense of what a palace was like when you walked in there."

Sometimes, however, even protective spirits need protecting. At some point since Nimrud's excavation, this genie relief was moved into a storage room from where it disappeared. It's believed to have been taken in the 1990s during the chaos of the first Gulf war, but no-one knows for sure.

The genie's whereabouts were completely unknown for about 10 years. Eventually in 2002, just before the second Gulf war, it turned up in London - one of the world's largest antiquities markets.

NYPL)

NYPL)

Scotland Yard's Art and Antiques Unit went to collect the genie, but it's unclear who legally owns it, so for the last 14 years it has been locked up in a secure storage unit belonging to London's Metropolitan Police.

"The problem is that the burden of proof on objects, when they are looted, is on the authorities to show that it really was removed illegally," says Altaweel.

This can be a challenge.

Looters sometimes lie about an object's country of origin, and move it through a variety of transit points. It may change hands many times and some of the sellers may insist on remaining anonymous.

"So the genie is basically in a kind of limbo state," says Altaweel.

Even though it appears to be part of a documented collection that was in Nimrud for 3,000 years, at present it seems unlikely to ever return to Iraq.

Brooklyn Museum)

Brooklyn Museum)

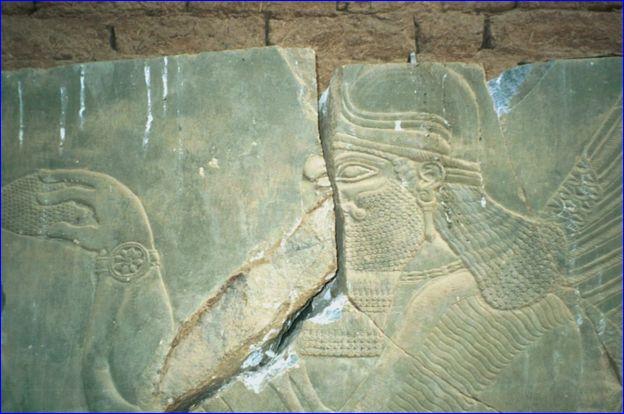

At some point in its journey, the genie was badly damaged. His head, wings, and upper body are still visible, but gone are his legs and much of Ashurnasirpal's cuneiform inscription. These may have been hacked away when the genie was first taken, or disposed of en route to London - it's not clear. But it is still highly valuable.

"We hear that just the head was going for £3.5m (almost $5m) in 2003 prices," says Altaweel.

"So imagine the value it would get today, and there are people who are willing to pay those prices. There has always been an interest in Nimrud."

Altaweel was in Nimrud just weeks after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and saw for himself fresh signs of looting.

"The site guard told me there was a gunfight that happened, with some bullets hitting the reliefs," he says. Some of the panels depicting genies and other figures had been cut out - the head would be missing, with the body and legs still in place.

The awful irony is that the looting of the genie now at Scotland Yard may have saved it from complete destruction. After seizing Mosul in 2014, the so-called Islamic State group began destroying sites in and around the city - including, the following year, Nimrud.

Mark Altaweel)

Mark Altaweel)

This has prompted debates about the thorny issue of repatriation. Some have argued that it might have been better if more of the Middle East's archaeological riches had been taken from the region during the era of European imperialism. To them, the iconoclasm of the would-be caliphate seemed to justify, in retrospect, the cavalier way in which Western archaeologists and collectors relieved the Middle East of its cultural heritage in the 19th and early 20th Centuries.

And yet for many people outside the West, it remains a source of grievance that so much of their past sits in the halls and basements of museums in Paris and Berlin, London and New York. Westerners can more easily enjoy the cultural history of Iraq than Iraqis themselves.

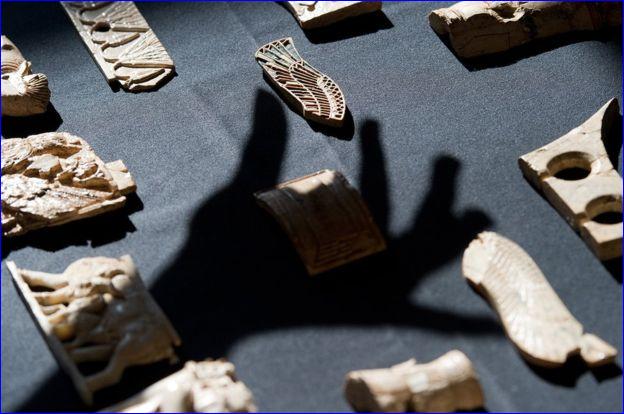

But while looters have plundered Iraqi museums and still threaten historical sites, the looted objects do not always end up being smuggled abroad.

Mark Altaweel)

Mark Altaweel)

Mark Altaweel was at the museum in Sulaymaniyah in Iraqi Kurdistan five years ago, when he got chatting to an American Kurdish man. Only after the man had left did Altaweel realise that a transaction had just taken place.

The visitor had offered to sell a series of cuneiform tablets and other objects and the museum at the time had a no-questions-asked policy, so it bought them.

"At first glance you think that's a horrible policy," says Altaweel. "But it did actually prevent them from leaving Iraq proper."

Getty Images)

Getty Images)

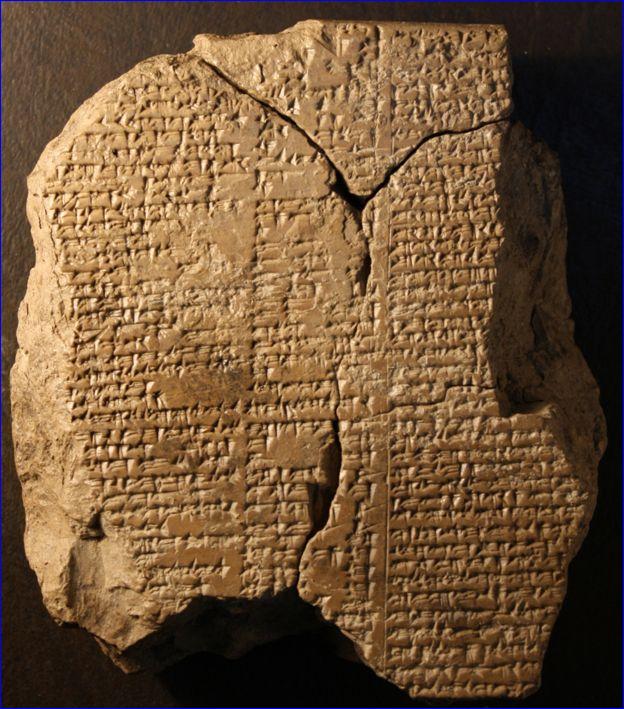

The visitor's haul included something amazing - a chapter of the Gilgamesh epic, the original blockbuster adventure, with monster battles, the search for immortality, divine kings, and even a whole section on how the wrathful gods flooded the Earth (a scenario that would appear again in the later biblical tale of Noah). Gilgamesh is humanity's earliest story. It marks that moment when gods and humans stepped out of the murky unknown and into the sharp relief of narrative.

"As soon as they saw that there's a text that talks about the Gilgamesh story, their immediate reaction was to buy this thing," says Altaweel. "They understood that this was extremely rare."

Farouk al Rawi)

Farouk al Rawi)

One of the key scenes in the Gilgamesh epic is the momentous encounter between the hero Gilgamesh and the monster Humbaba, described as a hideous ogre - his "roar is a flood, his mouth is death and his breath is fire!"

This beast of the wild can generally be found roaming the beautiful Cedar Forest. His primary aim is to terrify men and it's up to the brave, demi-god Gilgamesh and his sidekick Enkidu to vanquish Humbaba and rid the forest of his ugly tyranny. But what's remarkable about the Gilgamesh tablet recovered at the Sulaymaniyah museum is that it shows Humbaba in a different light.

"Where ?umbaba came and went there was a track, the paths were in good order and the way was well trodden," the tablet reads.

"Through all the forest a bird began to sing: A wood pigeon was moaning, a turtle dove calling in answer. Monkey mothers sing aloud, a youngster monkey shrieks: like a band of musicians and drummers daily they bash out a rhythm in the presence of ?umbaba."

In this version of the story, Humbaba is beloved of the gods and a kind of king in the palace of the forest. Monkeys are his heralds, birds his courtiers, and his entire throne room breathes with the heady aroma of cedar resin.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu, meanwhile, are aggressors, ecological thieves. They come to Humbaba's forest to take its timber back to their treeless homeland in Mesopotamia. In this newly discovered tablet of the epic, we find - remarkably - a sense that the heroes of the tale were in the wrong.

"Enkidu opened his mouth to speak, saying to Gilgamesh: 'My friend, we have reduced the forest to a wasteland. In your might you slew the guardian, what was this wrath of yours that you went trampling the forest?'"

This sense of remorse is particularly strong in the Sulaymaniyah tablet, but traces of it also exist in other versions of the Gilgamesh epic. In so many other ancient tales, the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf for example, we find a black-and-white world, a clear binary of good and evil. In Gilgamesh there is plenty of grey. The hero is faced with the moral consequences of his actions. There is so much destruction in the achievement of his greatness.

Intentionally and unintentionally, modern-day combatants in Iraq and Syria are destroying precious records of antiquity, and more objects like the genie and cuneiform tablets will inevitably slip on to the black market. So, it's worth celebrating the rare recoveries of these artefacts.

"It's a good and bad thing. It's bad that it was looted, it's bad that it had to be purchased. But it's good because at least it stays in the country of Iraq," says Altaweel.

"It's one of these things where Western scholars actually have to come to Iraq to see this and study this tablet. So it's good that at least something of significance stays in the country. Iraqis need to see these things too, ultimately these countries need stability, and stability equals economy, equals tourism, equals the objects being back there."

War makes exiles out of people and cultural artefacts alike. It is a small victory, but a victory nonetheless, when an antiquity like the tablet of Gilgamesh can endure and remain in Iraq.

Ashurnasirpal's genie, however, seems destined to stay far from its old home. Once it guarded the palace of its king. Now it is guarded by British police, in an obscure basement in a foreign country.

or register to post a comment.