The most famous colossal statues of Lamassu have been excavated at the sites of the Assyrian capitals established by King Assurnasirpal II (reigned 883 -- 859 BC) and King Sargon II (reigned 721 -- 705 BC). The winged beasts from Nimrud in Iraq (the ancient city of Kalhu) also became very famous when Lamassu there were damaged in 2015. Other statues of the mythical beasts belong to cities like ancient Dur Sharrukin (current Khorsabad, Iraq).

Every important city wanted to have Lamassu protect the gateway to their citadel. At the same time, another winged creature was made to keep watch at the throne room entrance. Additionally, they were the guardians who inspired armies to protect their cities. The Mesopotamians believed that Lamassu frightened away the forces of chaos and brought peace to their homes. Lamassu in the Akkadian language means "protective spirits."

Celestial Beings

Lamassu frequently appear in Mesopotamian art and mythology. The first recorded Lamassu comes from circa 3,000 BC. Other names for Lamassu are Lumasi, Alad, and Shedu. Sometimes a Lamassu is portrayed as a female deity, but usually it is presented with a more masculine head. The female Lamassu were called "apsasu."

Lamassu, as a celestial being, is also identified with Inara, the Hittite-Hurrian goddess of wild animals of the steppe and the daughter of the Storm-god Teshub. She corresponds with the Greek goddess Artemis.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh and Enuma Elis, both Lamassu and Aspasu (Inara) are symbols of the starry heavens, constellations, and the zodiac. No matter if they are in a female or male form, Lamassu always represent the parent-stars, constellations, or the zodiac. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, they were considered as protective because they encompass all life within them.

The cults of Lamassu and Shedu were very common in households from the Sumerian to Babylonian period, and they became associated with many royal protectors in different cults. Akkadians associated Lamassu with the god Papsukkal (the messenger god), and the god Isum (a fire-god, herald of the Babylonian gods) with Shedu.

Mythical Guardians that Influenced Christianity

Lamassu were protectors of not only kings and palaces, but of every single human being. People felt safer knowing that their spirits were close, so Lamassu were engraved on clay tablets, which were then buried under the threshold of a house. A house with a Lamassu was believed to be a much happier place than one without the mythical creature nearby. Archaeological research shows that it is likely that Lamassu were important for all the cultures which lived in the land of Mesopotamia and around it.

As mentioned, the Lamassu motif first appeared in royal palaces at Nimrud, during the reign of Ashurnasirpal II, and disappeared after the reign of Ashurbanipal who ruled between 668 BC and 627 BC. The reason for the Lamassu's disappearance in buildings is unknown.

Ancient Jewish people were highly influenced by the iconography and symbolism of previous cultures, and also appreciated the Lamassu. The prophet Ezekiel wrote about Lamassu, describing it as a fantastic being created of aspects of a lion, an eagle, a bull, and a human. In the early Christian period, the four Gospels were also related to each one of these mythical components.

Furthermore, it is likely that the Lamassu was one of the reasons why people started to use a lion, not only as a symbol of a brave and strong head of a tribe, but also as a protector.

Powerful Monuments

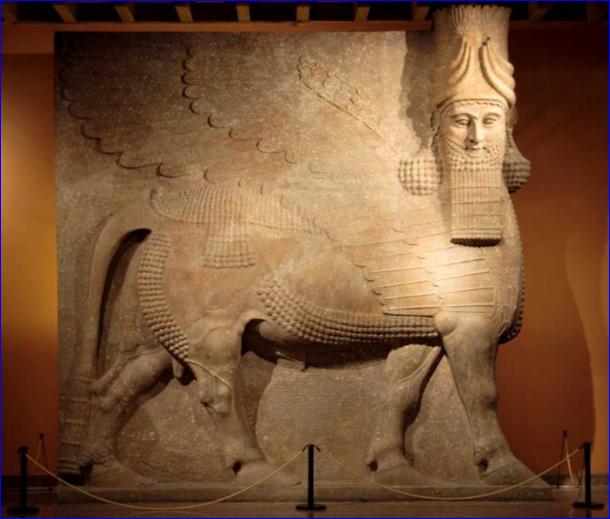

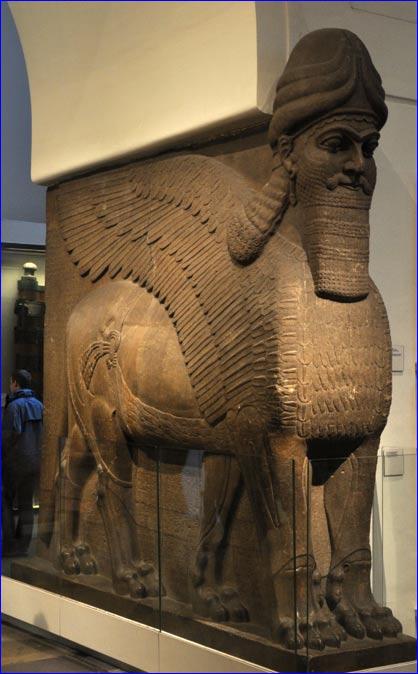

Nowadays, Lamassu are still found standing proud. They were carved from a single block. The oldest monumental sculptures are about 10-14 feet (3.05-4.27 meters) tall and they are made of alabaster. The most recognizable difference between the older Lamassu and the ones from a later period is the form of their body. The first Lamassu were carved with the body of a lion, but the ones from the palace of King Sargon II have a body of a bull. What's more interesting-- the Lamassu of Sargon are smiling.

In 713 BC, Sargon founded his capital, Dur Sharrukin. He decided that protective genies would be placed on every side of the seven gates to act like guardians. Apart from being guardians and impressive decoration, they also served an architectural function, bearing some of the weight of the arch above them.

Sargon II had an interest in Lamassu. During his reign, many sculptures and monuments of the mythical beasts were created. In this period, the body of Lamassu had a high relief and the modeling was more marked. The head had the ears of a bull, face of a man with a beard, and a mouth with a thin mustache.

During the excavations led by Paul Botta, in the beginning of 1843, archaeologists unearthed some of the monuments which were sent to the Louvre in France. This was perhaps the first time when Europeans saw the mythical creatures.

Currently, representations of Lamassu are parts of collections in the British Museum in London, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and The Oriental Institute in Chicago. During the operation of the British army in Iraq and Iran in 1942-1943, the British even adopted Lamassu as their symbol. Nowadays, the symbol of the Lamassu is on the logo of the United States forces in Iraq.

The motif of Lamassu is still very popular in culture. It appears in The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis, in the Disney movie Aladdin, in many computer games, and more.

or register to post a comment.