In Bonnyrigg in outer western Sydney, across the road from another McDonald's totem poking the sky, on scrappy land rescued from quarter-block Australian suburban contagion, a two-metre-long golden arm clutching a ball rises from a plinth of black stone slabs.

In Bonnyrigg in outer western Sydney, across the road from another McDonald's totem poking the sky, on scrappy land rescued from quarter-block Australian suburban contagion, a two-metre-long golden arm clutching a ball rises from a plinth of black stone slabs.

The sullen sheen of the bronze limb resembles a child's netball trophy swollen to ambitious proportions. It's nothing grand, but to the small Christian Assyrian community of Australia this memorial marks uprooting, mass murder, and the ultimate prize of a wandering people finding a safe place to call home.

"We are the indigenous people of Iraq, like the Aborigines are the indigenous people of Australia," says Hermiz Shehan, a 59-year-old businessman and community leader. "We looked for a site for a monument so that our people never forget what happened, and the continual struggle for getting the recognition of the genocide."

Shehan's background is typical of many Assyrians, whose community reflects much of the past and current turmoil of the Middle East, as well as a little-known chapter of Australian military history.

His paternal grandparents were killed during the Ottoman ethnic cleansing of Christians from Anatolia during World War I; his father had been separated forever from his own two-year-old brother in 1917. Shehan fought hard to bring his parents to Australia when he was granted refugee status in 1981. They arrived in 1983 after a journey from Iraq through Jordan, Syria, Turkey and Yugoslavia.

If life was bad for the Christian Assyrians under Saddam Hussein, he reckons they were worse after the US invasion in 2003: "This invasion or freedom of Iraq was a genocide for Christians. We brought an Islamic regime built on radicalism. Since 2003 they have destroyed around 70 churches in our country where we are the original people. There is a reason why we are worried about Australia."

He estimates that of Iraq's pre-2003 Christian population about half have fled for neighbouring countries, Turkey, Lebanon and Syria. "Imagine what will happen if an Islamic regime comes to Syria? Like in Egypt…" says Shehan, referring to recent attacks on Egypt's Coptic Christians following the Arab spring uprising.

Like so many of the inter-communal squabbles that form the rough edges of Australia's multi-ethnic mosaic, the application to Fairfield Council in Sydney's western suburbs to erect the Assyrian Genocide Memorial incensed many in the Turkish community; it provoked protests from the Turkish government.

"Probably some people told them it was against Islam, and they started motivating the Turks all over Sydney," says Shehan. Even Federal Labor MP for Liverpool Julia Irwin warned in parliament that the monument would "open a Pandora's box."

After official protests from the Turkish government, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Stephen Smith, wrote to the mayor of Fairfield to persuade him to shelve the vote.

"We told the mayor, 'Look, this is an insult to the Assyrian community, in this free country we've come under pressure from the Turkish government, we can't talk freely or respect our martyrs,'" Shehan says.

On December 15, 2009, with a contingent of police separating about 500 raucous Turkish and another 500-some Assyrian protesters outside, and an Assyrian deputy-mayor and five Assyrian councillors casting half the votes, the council approved the application. More than 3,000 people and 30 state and federal MPs were at the August 2010 unveiling. "[The] Minister for Immigration Chris Bowen was here," says Shehan, adding, "This isn't good for the Turkish government because it means officially the Australian government is recognising the genocide."

ALMOST 6,762 years of history looms over the shoulders of Carmen Lazar while she scribbles unperturbed. The Assyrian Resource Centre in Fairfield sits between an Arabic Iraqi kebab house and a small, smoke-filled, shop-front club filled with elderly Middle Eastern men playing board games and watching TV. Trains rattle past outside. A community settlement officer for the Assyrian community, Lazar seems to have a smile for everyone. The centre helps to resettle newly arrived Assyrians, as well as other walk-ins.

"We welcome everybody here, Arabs too, because we know how to speak to them," says Lazar.

On a wall behind her, the staunch-eyed Assyrian kings peer down from a two-metre-long plaster replica of one of the 2,500 year-old Assyrian stone carvings from the British Museum. It's a parade of half-bull, half-human royals, sporting rococo beards and stiff wings, strutting beneath the fluoro strip lights of Lazar's centre, where she is excitedly recounting her new appointment as one of dozens of ethnic advisors to the federal government. The centre is busy, with the doors flinging opening every few minutes as a breathless Lazar ushers out NSW Legislative Assembly member Andrew Roshan, an Assyrian Australian.

The Assyrian kings glorified their conquests and personal feats of arms with a brilliant legacy of gypsum slabs fixed to stelae and walls that radiated out across the deserts and oases from the ancient capital of Ninevah, on the upper reaches of the Tigris River in Northern Iraq.

"I dressed in my very best clothes," says Lazar, recounting her pilgrimage to see the original reliefs in London, where hundreds of metres of carvings depict regal lion hunts and priestly invocations to Ishtar. "My husband laughed and asked me what I was doing, but I felt I was in the presence of my kings," she says, her eyes widening.

The unearthing of Ninevah by French and British officials in the early 19th century is one of the great epics of archeology, and it provided solid foundations for the strengthening of an Assyrian national consciousness.

From around 2400BC, the reach of the Assyrian empire ebbed and flowed from the Mesopotamian river basin of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, as far as Egypt, the Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf, and north to the Caspian and Black seas. The discovery of Ninevah, and the apparent unbroken connection linking the bovine kings with modern Christian Assyrians, fired European interest in protecting the national minorities of the flagging Ottoman Empire.

The persecution of the Greek, Armenian and Assyrian Christian minorities began in earnest in the 1840s. During the First World War perhaps a million were killed. Proxy Kurdish forces burned people out of their villages, killed tens of thousands, and drove the remainder on forced marches into modern Armenia, Syria, Iraq and Iran.

Although the ethnic cleansing of Christians was acknowledged by the Turkish Republic's founder, Kemal Atatürk, and by the trial of some ringleaders in proceedings that quickly sputtered out, Turkey has always forcefully denied that it was official Ottoman policy, or that the crimes meet the legal definition of a genocide.

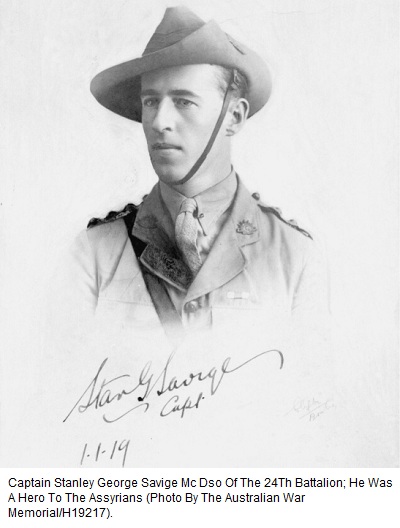

FAR AWAY from this bloodshed, in the town of Morwell, rural Victoria, an altogether smaller plinth supports the bronze bust and celebrates the Distinguished Service Order of Lieutenant General Sir Stanley George Savige.

FAR AWAY from this bloodshed, in the town of Morwell, rural Victoria, an altogether smaller plinth supports the bronze bust and celebrates the Distinguished Service Order of Lieutenant General Sir Stanley George Savige.

In July and August 1918, as a young Australian army captain, Savige and eight men held back hundreds of Kurdish and Persian fighters attacking a column of tens of thousands of helpless Assyrians fleeing the town of Urmia, which had just been captured by Turkish forces. The Australian military historian C.W.E. Bean described Savige's bold and solitary stands as, "fine as any episode known to the present writer in the history of this war."

"Savige went to help us from the Turkish slaughter," says Hermiz Shehan. "That's why Australia is totally aware of what happened to our people. The Anzacs knew all about it and wrote about it in letters."

Perhaps it paved the way. Since the first trickle of Assyrians began arriving in Australia in the mid-1960s, building to a current community of about 26,000, they have developed into a hard-working, modestly successful minority. Woven between mosques and Laotian temples around Bonnyrigg and Fairfield streets, there are three Assyrian churches, an Assyrian primary school, a high school, and three Assyrian social clubs that also reflect linguistic and religious distinctions amongst the Assyrians, Chaldeans and Syriacs.

But the sanctuary the Assyrians have found in Australia, hasn't been always entirely smooth despite the community's broadly cohesive and well-organised core, and the well-funded efforts of community outreach groups such as Lazar's. Like many of Australia's communities, it has its share of misfits, thugs and murderers.

In the waiting room of Fairfield police station, a smiling young police constable stares, from a framed photo, at the complainants and edgy parolees lined up at the front desk. The constable, David Carty, was 25 years old when, on 18 April 1997, he finished work at the station, took a drink with a colleague at a local bar, and after walking her to her car, was surrounded by a group of seven or eight men. He was beaten to the ground, and kicked and stabbed in the head. He appeared to have been partly scalped; a beer glass had been used to savage him, and a part of one ear and his nose had been sliced off. His assailants were Assyrians, a number of whom are doing lengthy stretches in prison.

For about four years from 2002, a series of murders, assaults and drive-by shootings in Fairfield were attributed to a gang of Assyrians called Dlasthr (The Last Hour). Gang members reputedly have a tattoo of a clenched fist etched on their back, with the letters AK, an acronym for Assyrian Kings. But relative to other larger gangs - Lebanese, Vietnamese, Pacific Islanders - the Assyrian gangs appear to have been a brief nuisance, with most damage done to Constable Carty and the Assyrian community itself.

Shehan dismisses Assyrian gang violence as an aberration in the community. "Pride of being Assyrian is something we have lost in our countries. We could not say that we are Assyrians, always persecuted," Shehan says. "If we mix with the wrong people, that's one thing, but nothing to do with our love of nation."

Shehan dismisses Assyrian gang violence as an aberration in the community. "Pride of being Assyrian is something we have lost in our countries. We could not say that we are Assyrians, always persecuted," Shehan says. "If we mix with the wrong people, that's one thing, but nothing to do with our love of nation."

He believes that the Australian immigration authorities should more closely pair ethno-religious community groups with immigrant constituents upon arrival in Australia, rather than the current practice he describes as simply cutting them loose into the community.

"Many of these boys spent times in refugee camps, with no authority. They need to be shown how to assimilate."

LOVE OF nation, of history, and of place comes easily to the Assyrians - but how does that translate to 21st century Australia?

For Shehan, his defensive passion of Assyrian identity has found, on occasion, shared caused with the stridently conservative NSW Christian Democratic Party of the MP, the Rev, Fred Nile, and with an abiding mistrust of Muslim immigration to Australia. A history of forced conversion, slaughter and displacement is not easily shaken off. He believes that Muslims are intentionally targeting Bonnyrigg for settlement. "The same thing happened in our country," he says. "When they came, Iraq was a totally Christian country. And today we are not even three per cent."

Sargis Makko is the 49-year-old principal of Fairfield's St Hurmizd Assyrian Primary School. Some 500 students attend the school, which sits behind the imposing light brick body of the St Hurmizd Cathedral of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East. Like many specialist community schools with religious foundations, the Assyrian students of St Hurmizd are instructed in English in the full standard curriculum, as well as NSW Education Board-approved studies in Assyrian language, history, culture and faith. Pupils graduate fluent in both the Latin and Aramaic alphabets.

One wouldn't guess from his broad Australian accent, but like many Assyrians Mako arrived as a 14-year-old, fresh from a refugee camp. He sees his role as teaching Australian kids about their background, in alignment with Australian values.

"That means respect for the law, tolerance, recognizing the rights of other faiths - but not forgetting, never forgetting," Mako says.

"That means respect for the law, tolerance, recognizing the rights of other faiths - but not forgetting, never forgetting," Mako says.

ON APRIL FOOLS' Day in 2012, the Assyrians of Sydney will celebrate the 6,762nd year of what they say is their unbroken civilisation with a festival at Fairfield Showground. The community mounts the fair every year on April 1.

Hopes of a national homeland governed by Assyrians, on land currently occupied by Kurdish Iraqis, haven't dimmed over the years. Members of the global Assyrian diaspora have made frequent representations for a self-governed province in Iraq, but with not even a jot of political progress. For the past decade, as the Iraqi Christian population has been bombed and burned out from their Iraqi villages, Shehan has met with Australian foreign ministers to make the Assyrian case.

"They tell us that they are monitoring the situation. What monitoring? There'll be no more Christians left in Iraq," Shehan says.

Meanwhile, the Assyrian community is monitoring its genocide memorial.

After completion in 2010, the memorial plaque was torn off, and graffiti of the Turkish star and crescent, along with various obscenities, spray-painted across the plinth and bronze arm. "We love our nation, which is why we paid a lot for it, not like some other nations that dissolved or assimilated into the Arab communities," says Shehan.

"We fought for Christianity, and we are paying a price for it. Why when it comes to the Assyrians, is there still silence?" he asks.

or register to post a comment.