After 2,700 years, the walls and gates of ancient Nineveh can still be seen near the banks of the Tigris river just opposite the modern city of Mosul in Iraq. In ancient times, it was the capital of the great Assyrian empire, a city of more than 100,000 people, and it was a subject of a supreme being's attention throughout the books of the Old and New Testaments in the biblical account. "Now the word of the Lord came unto Jonah the son of Ammittai, saying, Arise, go to Nineveh, that great city, and cry against it; for their wickedness is come up before me."[1] The prophet Jonah's efforts there were rewarded. Nineveh, at least for a time, was saved from destruction. But the city of Nineveh today will require a different kind of saving. There are comparatively few people living there now. It features mostly ruins. Even the ruins, however, will disappear unless, according to the Global Heritage Network's early warning system, urgent steps are taken to arrest the elements that endanger it and to restore and protect what is left.

After 2,700 years, the walls and gates of ancient Nineveh can still be seen near the banks of the Tigris river just opposite the modern city of Mosul in Iraq. In ancient times, it was the capital of the great Assyrian empire, a city of more than 100,000 people, and it was a subject of a supreme being's attention throughout the books of the Old and New Testaments in the biblical account. "Now the word of the Lord came unto Jonah the son of Ammittai, saying, Arise, go to Nineveh, that great city, and cry against it; for their wickedness is come up before me."[1] The prophet Jonah's efforts there were rewarded. Nineveh, at least for a time, was saved from destruction. But the city of Nineveh today will require a different kind of saving. There are comparatively few people living there now. It features mostly ruins. Even the ruins, however, will disappear unless, according to the Global Heritage Network's early warning system, urgent steps are taken to arrest the elements that endanger it and to restore and protect what is left.

Not an easy thing to do these days in a war-torn country. War has distracted and preoccupied the energies of a people who otherwise could be identifying and procuring the necessary resources needed to save and protect the city.

But long before war, it has been plagued by looting and vandalism. Artifacts have appeared on international markets for sale, reliefs have been marred by vandalism, and chamber floors have seen holes dug into them by looters hoping to find anything that will yield cash for their needs. The expanding suburbs of adjacent Mosul, too, threaten it with encroachment, with sewer and water lines having already been dug and new settlements already established within the area once occupied by the ancient city.

Even without looting, vandalism and suburban encroachment, however, Nineveh will crumble and succumb to the natural elements. Reports the Global Heritage Fund (GHF)*, a non-profit organization that specializes in saving and restoring archaeological sites, "without proper roofing for protection, Nineveh's ancient walls and reliefs are becoming more and more damaged by natural elements every day. Exploration of the city is an important objective at this time, but preservation measures would go a long way as well".[2]

Historically, the site of ancient Nineveh, which consists of two large mounds, Kouyunjik and Nabi Yunus ("Prophet Jonah"), has been the subject of numerous excavations and exploratory expeditions since the mid-19th century. Beginning with French Consul General at Mosul, Paul-Émile Botta in 1842, and most notably through the excavations of famous British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard (pictured right) and many others thereafter, the remains of Nineveh became one of the sensational archaeological revelations of modern times. Before that, Nineveh, unlike the clearly visible remains of other well-known sites such as Palmyra, Persepolis, and Thebes, was invisible, hidden beneath unexplored mounds. Even historical knowledge of the Assyrian Empire and its capital city was sparse in the beginning, changed primarily by the great archaeological discoveries that followed Botta's initial attempts. One palace after another was discovered, including the lost palace of Sennacherib with its 71 rooms and enormous bas-reliefs, the palace and library of Ashurbanipal, which included 22,000 cuneiform tablets. Fragments of prisms were discovered, recording the annals of Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal, including one almost complete prism of Esarhaddon. Massive gates and mudbrick ramparts and walls were unearthed. The walls encompassed an area within a 12-kilometer circumference. Many unburied skeletons were found, evidencing violent deaths and attesting to the final battle and siege of Nineveh that destroyed the city and soon brought an end to the Assyrian Empire.

Despite its long history of excavation, the ancient site of Nineveh leaves much to be explored. But conservationists and others are arguing that further excavation and exploration would be pointless without a concerted, meaningful plan and efforts to preserve the finds for posterity, beginning first with what has already been uncovered. "Nineveh has already been heavily attacked by looters, and now development pressures from nearby Mosul have begun to take their toll as well," reiterates GHF. "If this encroachment continues, Nineveh's ancient remains could again be buried forever."[2]

In an October 2010 report titled Saving Our Vanishing Heritage, Global Heritage Fund designated Nineveh among the top 12 sites in the world most "on the verge" of irreparable loss as a result of looting, development encroachment, and insufficient management of its cultural resources.

[1] Jonah 1: 1-2

[2} Nineveh, Iraq: Ancient Jewel of the Assyrian Empire, Heritage on the Wire, Global Heritage Fund, October 26, 2010.

Photo, second from top, right: Drawing of excavations of Nineveh, Wikimedia Commons.

Cover photo, top left: The Mashki Gate, Lachicaphoto, Creative Commons.

The Glory That Was Nineveh

Nineveh first enters the historical record in about 1800 BCE as a center of worship of Ishtar, which established the city as an important religious center. It was during the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, particularly from the time of Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BCE) onward, that the city witnessed its first great architectural expansion. Thereafter, the monarchs Sargon II, Esarhaddon, Sennacherib and Ashurbanipal established new palaces and temples to Sin, Ashur, Nergal, Samas, Ishtar, and Nabiu of Borsipa. It was Sennacherib, however, who elevated Nineveh to great prominence (c. 700 BCE). He created new streets and squares and constructed his magnificent "palace without a rival", remains of which have been recovered, showing dimensions of about 503 by 242 meters (or 1,650 × 794 ft). The stone carvings on the walls of his great palace illustrated battle scenes, impalings and scenes of conquests, with his army parading the spoils of war. He wrote of his conquest of Babylon: "Its inhabitants, young and old, I did not spare, and with their corpses I filled the streets of the city." And Lachish in Judea: "And Hezekiah of Judah who had not submitted to my yoke...him I shut up in Jeruselum his royal city like a caged bird. Earthworks I threw up against him, and anyone coming out of his city gate I made pay for his crime. His cities which I had plundered I had cut off from his land."

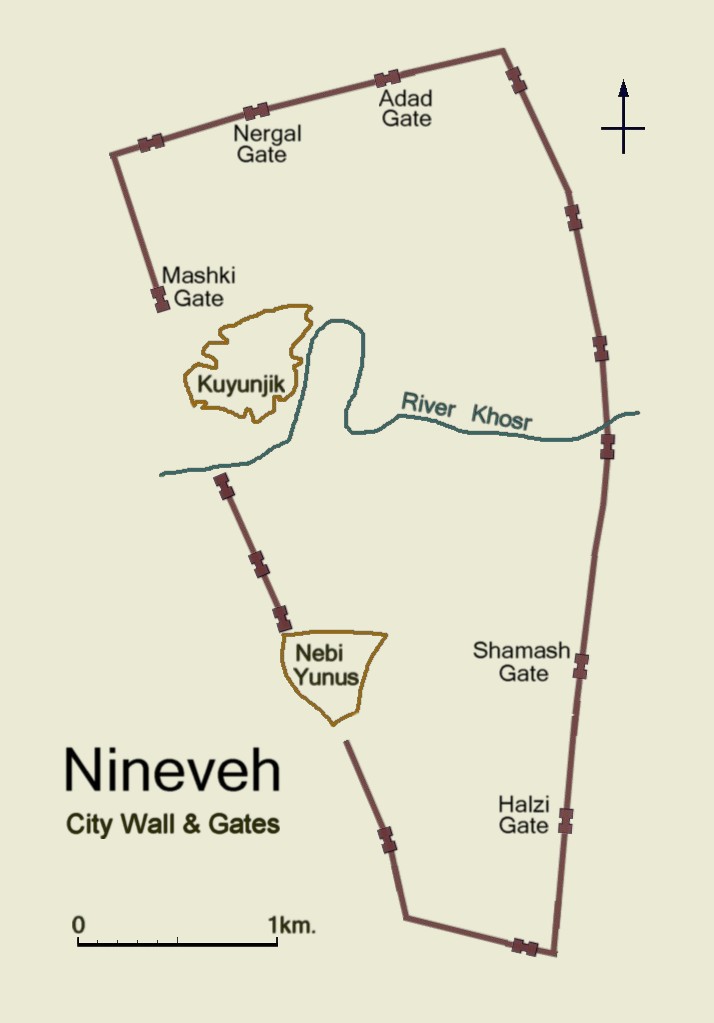

At the height of its glory, Nineveh covered 7 square kilometers (1,730 acres, see plan, right). Fifteen monumental gates were integrated within its walls. An elaborate canal system and aqueducts transported water from the highland areas into the city. Its area accommodated more than 100,000 inhabitants, far surpassing even Babylon at the time.

But Nineveh's greatness did not last long. In 627 BCE, following the death of Ashurbanipal, the empire began to weaken as a result of a series of civil wars. A weakened Assyria was then attacked by former vassals, the Babylonians and Medes who, in a concerted campaign with the Scythians and Cimmerians, sieged and sacked Nineveh in 612 BCE, completely destroying the city and massacring or scattering its inhabitants. Nineveh never again returned to its former status and splendor. Archaeological excavations have uncovered evidence of the siege and destruction, including numerous skeletal remains left unburied with tell-tale signs of violent death.

The Mashki Gate as it appears today. Lower stones are original, but much of the rest is reconstructed. Lachicaphoto, Creative Commons licensed 2010.

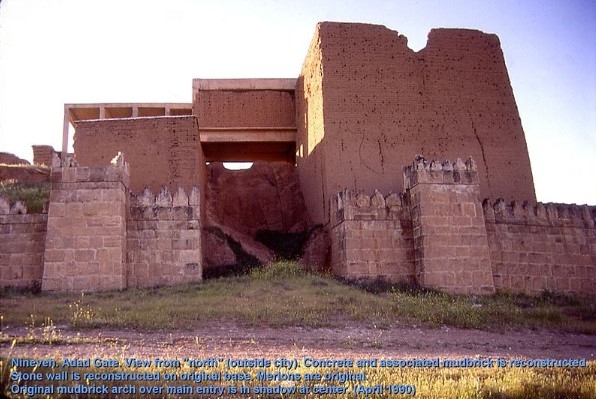

The Adad Gate (above), reconstructed on original foundation. Fredarch/Zunkir, GNU Free Documentation License

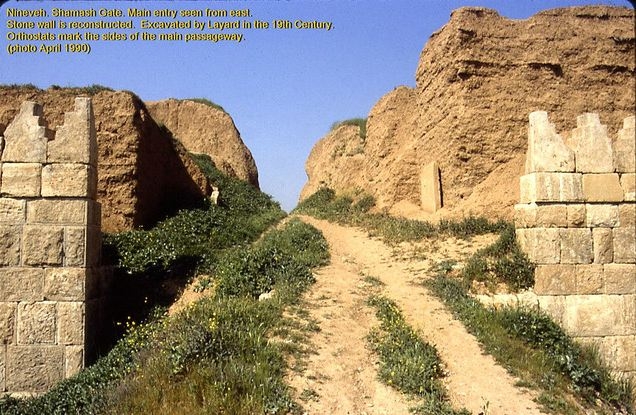

The reconstructed Shamash Gate. Main entry to the city as seen from the east. StevenB, Creative Commons

A sculptured relief from Ashurbanipal's palace. Courtesy British Museum and Martin Beek, Creative Commons.

The Royal Lion Hunt (above) at the British Museum from the North Palace Nineveh 645-635BC. The king is shooting arrows while attendants repulse an attack from a wounded lion. Mark.murphy CC-BY-SA-3.0-MIGRATED; Released under the GNU Free Documentation License

The crumbling remains of a palace sculpture. JoAnn S. Makinano, U.S. Air Force; Public Domain

Photo, in inset above right: Simplified plan of ancient Nineveh showing city wall and location of gateways. Image created by Fredarch under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.

or register to post a comment.