|

SHALL THIS NATION DIE?

BY

Rev. JOSEPH NAAYEM, O.I.

With a Preface by

LORD BRYCE

and

An Historical Essay by

Rev. GABRIEL OUSSANI, D.D.

Chaldean Rescue

253 Madison Avenue

New York, N.Y.

Published 1920 A.D.

Assyrian International News Agency

Books Online

www.aina.org

PREFACE

BY

LORD BRYCE

The bloodstained annals of the East contain no

record of massacres more unprovoked, more widespread or more terrible

than those perpetrated by the Turkish Government upon the Christians of

Anatolia and Armenia in 1915. It was the sufferings of the Armenians

that chiefly drew the attention of Britain and America because they

were the most numerous among the ecclesiastical bodies, and the

slaughter was, therefore, on a larger scale. But the minor communities,

such as the Nestorian and Assyro-Chaldean churches, were equally the

victims of the plan for exterminating Christianity, root and branch,.

although the Turks had never ventured to allege that these communities

had given any ground of offense. An account of these massacres,

organized and carried out with every circumstance of cruelty by Enver

and Talaat, chiefs of the ruffianly gang who were then in power in

Constantinople, has been given in the Blue Book, published by

the British Foreign Office in 1916, and entitled " Treatment of the

Armenians in the Ottoman Empire." In the present volume there is

presented a graphic and moving narrative of similar cruelties

perpetrated upon members of the Assyro-Chaldean Church in which about

half of them, men, women and children, perished at the hands of Turkish

murderers and robbers. The narrative is written by the Rev. Father

Naayem, who saw these horrors with his own eyes and narrowly escaped

with his life. He has recounted to me and to other friends of his

people in En land the terrible story, and we have encouraged him to

believe that his English translation of his book will be read with

sympathy and pity both here and in the United States. I venture to

recommend it to those who wish to know what these innocent victims have

suffered, trusting that it may do something to sustain that interest in

the sorely afflicted Christian Churches of the East, which has been

manifested in both countries, and hoping also that the charitable aid

so generously extended to them in their calamities may be continued.

The need of relief is still very great and it is for their Christian

faith, to which they have clung during centuries of oppression and

misery, that they have now again had to suffer.

23rd July, 1920.

AN HISTORICAL ESSAY

ON THE

ASSYRO-CHALDEAN CHRISTIANS

BY

REV. GABRIEL OUSSANI, D.D.

The Rev. J. Naayem, the author of this work,

and an eye-witness of most of the horrible scenes of massacre herein

described, has requested me to write an introduction to this English

version of his book for the benefit of the American public, which is

perhaps not so well acquainted with the history, geography and religion

of the Assyro-Chaldean Christians who suffered during and after the

great war (1915-1920) at the hands of the unscrupulous Turks,

indescribable tortures, and who lost through murder and famine 250,000

of their membership.

Having the interest and the welfare of this

unfortunate nation at heart, being myself a native of that unhappy

land, and having already known of these things through direct

correspondence with bishops, priests, merchants, friends and relatives

in Mesopotamia, I gladly accede to his request, hopeful of awakening in

the loving hearts of the American people a genuine sympathy and

commiseration for this martyred race, one of the most ancient and

glorious nations; but, alas, decimated and reduced to ruin.

Never in the past have the American people had

such an opportunity of extending a helping hand to oppressed Christian

nations as they have at the present time in Upper Mesopotamia.

The sufferings of the Belgian, French, Polish,

Serbian and Austrian peoples during the great war completely fade away

by comparison with what the helpless countries of the Near East

suffered and endured, and are still enduring, from Turkish and Kurdish

ravages and cruelties.

The excellent work done by the Near East

Relief Committee has accomplished much; but a great deal more must be

done, and done quickly, if the Christianity of the Near East, and

especially of Mesopotamia and Persia, is to be rescued from immediate

and total destruction. The well-merited relief so generously extended

to the suffering Armenians has in a way so completely focused the

attention and the generosity of the American people on this unfortunate

race, that the other,-smaller, but just as unfortunate,-races of the

Near East have been to a great extent lost sight of. These smaller

Christian nations, and particularly the Assyro-Chaldeans, suffered as

much at the hands of the Turks as the Armenians, and proportionately

more, and thus deserve as much sympathy and help.

Ethnographically, the modern Assyro-Chaldeans

are the descendants of the Ancient Babylonians, Assyrians and Arameans,

who for many millenniums inhabited and ruled over the Tigris-Euphrates

valley, Upper Mesopotamia and Syria, and who were the political masters

of the Near East for many centuries before the Christian era.

With the downfall of the Kingdoms of Assyria

and Babylonia (7th and 6th centuries B. C., respectively) and the

political ascendancy of the Medians, Parthians, and Persians (from

circa 6th century B. C. to 6th century A. D. especially during the

reign of the Sassanide dynasty), they suffered many political and later

on religious persecutions, but stood the test heroically.

Incidentally, their very ethnographic identity

and their national spirit of independence were completely crushed. They

were, so to say, engulfed in the many religious, racial and political

whirlpools and currents which swept over their country for more than

ten full centuries.

Under the Arab domination (from the 7th to the

13th century A. D.) they once more prospered, and developed the

greatest and most extensive Christian Church of the Near East, enjoying

vast political and religious privileges, marred at times by occasional

and local adversities. From the 13th century on and until our own day,

however, this heroic Christian nation suffered such untold misery and

persecutions at the hands of the cruel Tartars, Moguls and Mohammedan

Turks that at the beginning of the 20th century this once great and

fertile country, this glorious and powerful nation, was reduced to less

than one-tenth of its former size.

The Assyro-Chaldean nation embraced

Christianity, if not during the first, certainly during the middle of

the second century. Setting aside the controversy as to the early

evangelization of Edessa in Upper Mesopotamia during the reign of King

Abgar (circa 35 A. D.) and the traditional propagation of the Gospel

throughout Mesopotamia by the Apostles Thomas, Addai and Mari, it is

unanimously agreed by all ,scholars that towards the end of the second

century the Christian religion bad penetrated into the whole country

inhabited by the Assyro-Chaldeans. In the third and fourth centuries,

they already possessed a highly developed and well organized hierarchy,

with numerous dioceses and churches, a Patriarchal See, stationed at

Seleucia-Ctesiphon on the lower Tigris and a Christian population

exercising, at times, a far-reaching political and religious influence

over the Sassanian dynasty of Persia and the Arabian dynasty of Hira.

During the fourth, fifth and sixth centuries, the Assyro-Chaldean

Church became so extensive and powerful that it excited the fear and

the hatred of the Sassanian kings of Persia, who determined to

exterminate it with a series of almost uninterrupted persecutions and

unheard-of cruelties. Hundreds of thousands of martyrs gave their lives

willingly for the faith of Christ. Patriarchs, bishops, priests,

virgins, widows, children and adults, noble and poor, vied one with the

other in their faith and love for Christ, and were massacred with

tortures the like of which was not even dreamed of by the most cruel of

Roman emperors. And if the number of martyrs in the Roman Empire during

the first three or four centuries, according to a generous' estimate,

may have reached the grand total of 200,000, that of the

Assyro-Chaldean martyrs in the Persian Empire, from the 3rd to the 7th

century, must have reached the half million mark and perhaps twice that

number. Entire cities and whole districts were destroyed and their

Christian inhabitants slaughtered.

Monasticism also penetrated and flourished

early among the Assyro-Chaldean Christians. The mountains of Assyria

and Kurdistan teemed with hundreds of their monastic institutions, and

their inmates equaled and often surpassed the most austere and absurd

asceticism of the early Egyptian and Syrian monks and anchorites. Great

schools of theology and philosophy also flourished within this great

Church, and it is a well known fact that Arabian philosophy,

mathematics, medicine, the arts and the sciences of the Middle Ages,

though to a great extent of Greek origin, penetrated the Abbaside

Empire through the influence of the numerous Nestorian and Jacobite

scholars and schools of learning; and thus preserved Western culture

from utter destruction and ma de possible its reintroduction into

Europe through Spain at the hands of the Mohammedan Arabs.

Up to about the middle of the 5th Christian

century, the Assyro-Chaldean Christians professed the same orthodox

Christian Faith. In 429, Nestorius, a native of Syria and Patriarch of

Constantinople, began to preach his doctrine that in Christ there were

two distinct persons, (the human and the divine) just as there were in

Him two distinct corresponding natures, and thus denying the Divine

Maternity of the Virgin Mary. Condemned by the Council of Ephesus (431)

and repudiated by the whole Church of the West, and finding no outlet

for his doctrine in the Roman Empire, Nestorius, or rather his Syrian

followers and admirers, bishops, priests and monks, found in

Mesopotamia and Persia a fertile field for their teaching. Aided by the

Sassanian kings of Persia, the inveterate enemies of the Roman Empire

and of Western Christianity, they succeeded in propagating Nestorianism

throughout the length and breadth of the Persian Empire, with the

result that within a few decades the vast and powerful Christian Church

of Persia embraced the Nestorian doctrine and thus separated itself

from the Christianity of the West, becoming an autonomous church.

Hardly had this been accomplished when a new

christological heresy appeared on the horizon,-that of Eutyches,

another Syrian monk, and Abbot of Constantinople. In his opposition to

Nestorianism, Eutyches ended by propounding the opposite theory to

Nestorius, by maintaining that as in Christ there was but one Person,

so also His two natures became so thoroughly united or admixed as to

form but one composite nature. He was deposed and his doctrine

condemned by the Councils of Constantinople (448) and of Chalcedon

(451).

Finding again no outlet in the West, this new

teaching began to spread in Syria, Egypt, Armenia, Mesopotamia and

throughout the Persian Empire, rivaling in its rapid spread

Nestorianism itself; with the result that throughout all the following

centuries and till our own days, Assyro-Chaldean Christianity, which in

the 10th and 11th centuries boasted of not less than five hundred

dioceses, thousands of churches and millions of adherents, reaching in

its extension from Central Asia' China, Tartary, Mongolia, India

(Malabar), Mesopotamia, Persia, Syria, Cyprus and as far as Egypt,

became divided into two great rival Churches, viz., the Nestorian

Church, and the Eutychian or Jacobite Church.

From the 14th century, however, and as late

as, our own day, missionaries from religious orders of the Roman

Catholic Church centered their activities on converting these people,

with the result that ever since, and for the last six centuries

hundreds of thousands of these Assyro-Chaldean Nestorians and Jacobites

entered the Roman Catholic Church, preserving, however, their own

national and ecclesiastical language, liturgy, church discipline and

customs. At present, therefore, the Assyro-Chaldean Christians are

divided into four big sects or churches, with their own corresponding

hierarchy and distinct church organization and government, differing

but slightly in their faith, in their liturgy and liturgical language

(rather dialects of the same language), church discipline and

ecclesiastical customs.

At the beginning of the great war, according

to more or less reliable statistics, the total number of the

Assyro-Chaldean Christians in Turkey and Persia was about seven or

eight hundred thousand, scattered ,over the plains of Babylonia,

Mesopotamia, Upper Syria and the mountains of Assyria, Kurdistan and

Persia, whereas at the present time, having lost more than 250,000

souls at the hands of the tyrannical Turks, Kurds and Persians, they

hardly number 500,000, many of whom had to abandon their country and

homes and flee into Russia, Syria and lower Mesopotamia.

They are the following:

1.The Nestorian-Assyro-Chaldeans - commonly

Called Nestorians.

2.The Catholic Assyro-Chaldeans - commonly

called Chaldeans.

3.The Eutychian Assyro-Chaldeans - commonly

called Jacobites.

4.The Syrian Catholic Assyro-Chaldeans -

commonly called Catholic Syrians.

Numerically:

No. 1 before the war numbered circa 250,000.

No. 2 before the war numbered circa 150,000.

No. 3 before the war numbered circa 250,000.

No. 4 before the war numbered circa 50,000.

Owing to the staggering losses, it is almost

impossible to give accurate statistics of the Assyro-Chaldean

Christians at the present time. When the whole tale of destruction is

told and the condition of the country becomes normal (keeping in mind

the horrible slaughter of 250,000 souls, the total destruction of the

churches, the burning of thousands of homes, the killing of a dozen or

more bishops and hundreds of priests, the plunder and spoliation of

public, private and church properties, the ravages of hunger,

starvation, violence, disease, poverty, deportation, tortures,

amputation and mutilation of thousands still alive and rendered

helpless and in a state of abject poverty, ridicule and shame), then,

and only then, will the American people be enabled to form an adequate

estimate of the terrific losses in property and human life, in domestic

and personal happiness, in religion and education among the unfortunate

Assyro-Chaldean Christians.

For this reason Father Naayem's book is of

timely interest, as it will give the American public an accurate,

though meager pen picture of the horrible sufferings of but a small

portion of the Assyro-Chaldean Christians. .

America and American principles of justice and

liberty, American love for suffering humanity and American charity are

the only hope of stricken Eastern Christianity and the one bright star

in the once brilliant, but, alas, now darkened Eastern sky!

ST. JOSEPH'S SEMINARY,

Dunwoodie, N.Y.

Oct. 1st, 1920.

AUTHOR'S PREFACE

Several works have already appeared on the

atrocities and massacres perpetrated by the Turks in Armenia,

Asia-Minor and Syria. Eyewitness and victim of these cruelties, I come

in my turn to present my testimony. It is my heartfelt wish to reveal

to the public yet one more prey of the Monster of Anatolia;-the brute

whose history is one of felony, pillage, destruction, murder and

massacre;-the beast whose life has been prolonged by fifty years

through the action of the Great Powers to the ruin of the unhappy

Christians, ground for centuries beneath his heel. I desire to plead

the cause of a little people as deeply interested as it is abandoned; a

nation descended from a great Empire and from the most ancient

civilization known to history; a race whose country, like that of

Armenia, has been the theatre of abominations practiced by the Turks,

who have assassinated its men and deported the women, children and

graybeards to be subjected to the worst of outrages, and martyred with

cold and cruel calculation. That little people is the Assyro-Chaldean

race.

In this work will be found:

My account of the massacre of the Christians

in my own district of Urfa, the ancient and celebrated city of

Mesopotamia (better known perhaps in history by its former name,

Edessa). I recount the tragic fate of my father, victim of Turkish

hatred, and my own flight from Urfa.

In 1895-96, as a child of seven, I had

witnessed, in this same city of Urfa, the butchery of 5000 Christians,

whose throats were cut by their Turkish fellow-citizens. On that

occasion, thanks to some Arab merchants, his faithful friends, my

father had escaped the massacre.

An

account of my imprisonment and sufferings at the hands of these human

demons in the concentration camp of the Allied prisoners of war at

Afion-Kara-Hissar, to which I had been appointed Chaplain by the

Turkish Government at the request of the Holy See. An

account of my imprisonment and sufferings at the hands of these human

demons in the concentration camp of the Allied prisoners of war at

Afion-Kara-Hissar, to which I had been appointed Chaplain by the

Turkish Government at the request of the Holy See.

The testimony of a German of sincerity, one of

that nation whose government is not itself altogether guiltless of

complicity in the tragedy.

Documents confided to my care and detailed

narratives given me personally by eyewitnesses or actual victims of the

persecution who survived, miraculously, their sufferings.

Three hundred pages stained with human blood!

A story full of horrors and degradation in which the Turk reveals

himself for what he is; - a double-dealing fanatical hater of the

Christian.

I should like to quote a few lines from a

letter written to me on the 31st of May 1919, by a Frenchman who had

passed more than three years among the Turks as a prisoner of war:

"…I received your letter just at the moment

when you were giving your lecture, and was with you in spirit as I

thought of what you had to say as you retraced the unheard-of suffering

of the poor people who, during the war, lay prone under the

Turco-German whip. But have you told everything? Did you witness over

there all the misery and sufferings of those unhappy people? I saw them

in camp on their way through Kara-Pounar, a flock of miserable,

bleeding, starving, fever-riddled wretches, living skeletons who had

not even strength enough to dodge the cudgels of their murderers. How I

should have applauded had I had the good fortune to be among your

audience and hear you show up those butchers! …"

Would that I could bring to light the details

of the martyrdom of the Assyro-Chaldeans in the district of Djezire on

the Tigris and of Mediat, where over fifty villages I know were

completely sacked and ruined, all the inhabitants being put to the

sword: - a district which was fertile and prosperous and looked forward

to a happy future, because of the fact that the Baghdad Railway was

about to run through their territory.

There is not the slightest doubt that not less

than 250,000 Assyro-Chaldeans, perhaps rather more than a third of the

race, perished through Turkish fanaticism during the Great War, and

immediately after the signing of the Armistice.

During the occupation by the Allied Armies, in

June and July, 1919, two other Chaldean districts, Amadia and Zakho,

not far from Mosul, which until that time had been preserved by the

frenzied efforts of the Patriarch of Babylon, were invaded by the

Kurds, who put the men to death, and, after pillaging and sacking

everything, rode off with the women and girls. A letter from the

Patriarch, given me by his Vicar General at Rome, Mgr. Paul David, and

which I published in the press, briefly relates the details of this new

horror.

Today the situation of this little nation is

indeed precarious, surrounded as it is by a thousand fanatical and

hostile Arab and Kurd tribes, which are still armed and seem

contemptuous of the small Allied forces sent to maintain order. At the

first opportunity they will fall upon our unhappy countrymen and

exterminate the race.

In desperation we launch our appeal to the

pity and the justice of the Great Allied Powers, whose aim it is to

safeguard the rights of little nations, and we pray that they will not

delay in offering efficacious protection to this little Assyro-Chaldean

people which for centuries has groaned in slavery and oppression.

Confidently we hope and trust that they will assuage its misery,

mindful of its attachment to their cause, and will at length restore to

it its fatherland, its liberty and its autonomous existence.

J. NAAYEM.

CONTENTS

PART I

CHAPTER Page

1. My Father's Death 1

II. My Escape 25

III. The Fate of Urfa 39

IV. My Prison Experiences 43

V. My Successor's Experience 113

PART II

CHAPTER

I. Depositions Concerning the Massacre at

Sairt 121

II. Halata 145

III. Karima (aged 13) 163

IV. Stera and Warena 167

V. In the Desert 171

VI. The Massacre of Diarbekir 181

VII. In the Tents of the Bedouins 191

VIII. The Massacre of Lidja 199

IX. What Happened in Kharput 207

X. Rape, Loot, and Murder 217

PART III

CHAPTER

I. In Hakkiari and Persia 261

III. The Experience of the Right Reverend

Petros Aziz, Bishop of Salmas 303

ILLUSTRATIONS

Page

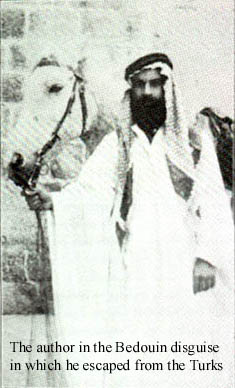

The Author Disguised as a Bedouin Frontispiece

The Author's Father 22

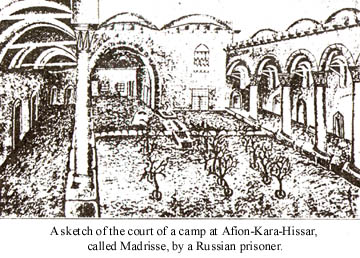

The Prison Camp 44

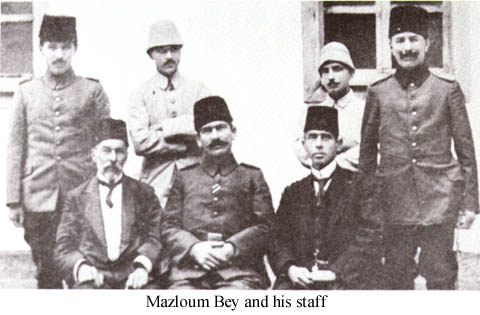

Mazloum Bey 53

The Patriarch of Babylon 121

Djalila 131

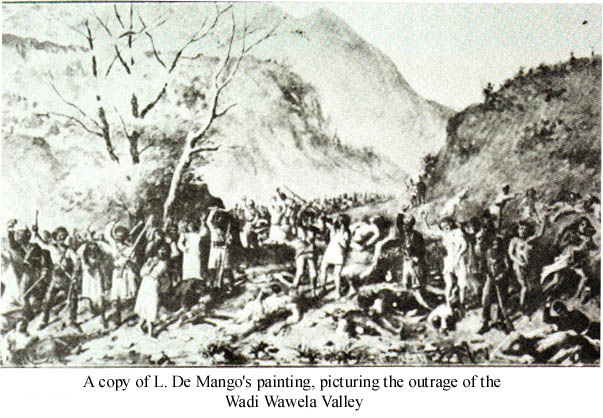

Wadi Wawela 139

Halata 145

The Archbishop of Sairt 158

The Archbishop's Secretary 162

Karima 163

Stera and Warina I 167

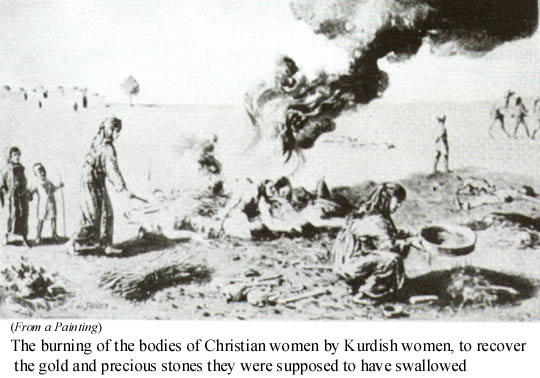

Hunting for Gold 172

The Archbishop of Diarbekir 181

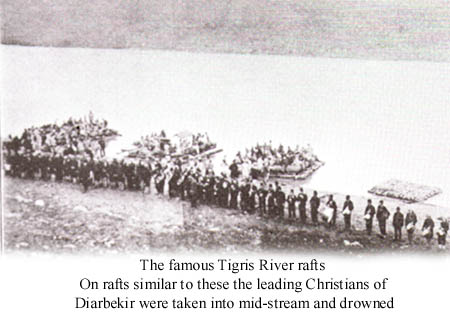

Rafts on the Tigris 187

Michael and His Brother 191

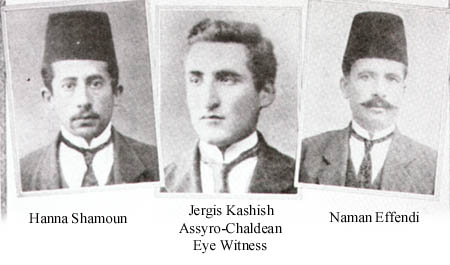

Eyewitnesses 199

The Archbishop of Jezire 207

Habiba 254

Mar Shimoun 261

The Rev. Lazare Georges 267

The Bishop of Salmas 303

The Bishop of Urmia 308

Map of Mesopotamia 318

PART 1

CHAPTER I

My

Father's Death My

Father's Death

At the commencement of the Spring of 1915, I

was in my parish at Urfa. The Great War was still in its early stages.

The Russians in the Caucasus were advancing with great strides, and the

Christians followed their operations with great interest, for they

preferred Muscovite to Turkish rule.

One day, while I was paying him a visit,

Bishop Ardawart showed me a map, pointing out with great satisfaction

the progress of the Russians in their march on Erzerum. This happened

some days before the-arrest of the leading men of the town; and the

poor Bishop had no premonition whatever of the fate awaiting him.

Propaganda of Armenian treachery was circulated. The faces of the Turks

changed and became more threatening. Photographs, purporting to show

Christians killing Turks, were passed from hand to hand in the police

stations, where they were shown -to the Turkish populace in order to

excite their fanaticism. It was alleged that bombs and rifles were

found in Christian houses and churches.

In March 1915, there began to arrive at Urfa,

in the most pitiable state, convoys of women, children and old men who

were being deported. The girls and pretty women had been carried off

while on the road, and the men had been separated from them or killed.

To prolong the wanderings of the unfortunate people, and to make them

spend all they possessed, they were compelled to halt several days at a

time. This gave the Moslem population sufficient time to besiege the

convoy, and appropriate for nominal prices whatever they wanted. At the

same time, the soldiers and police, who monopolized the trade with the

convoys, charged exorbitant sums for the provisions they had to buy.

They did worse, for at night they scaled the

walls of the large yard in which the Christians were kept, selected

various women and girls and carried them off across the flat roofs of

the houses. After being kept for some days as playthings, the wretched

creatures were then abandoned or massacred.

The yard where the convoys were taken soon

became infested with vermin, and rank with refuse, so that for several

months from ten to fifteen people died every day. The bodies were piled

on carts and taken outside the town, and thrown into ditches. Those who

had the strength wandered about the streets, ill and in rags, reduced

to begging their bread. Whenever I went out, I met many of these poor

people, the sight of whom unnerved me, and I would hasten home again,

sick at heart, obliged to refuse alms, to my intense mortification, to

so great a number. Many fell in the streets and died there of

starvation, their deathbed one of mud or dust.

Aye! These eyes of mine have seen little

children thrown on manure heaps, while life still lingered in their

little bodies.

The Armenian Bishop, although assisted by the

members of his community, was unable to cope with all this misery, for

the convoys multiplied in number. As soon as one had passed, after

being pillaged and ill-treated, another followed, and the same

heart-rending scenes were repeated, again and again.

This state of things, far from touching the

hearts of the Turks, increased their fanatical hatred toward the

followers of Christ. In the bazaars, the cafes,- everywhere,- one saw

them whispering together, planning foul surprises for the Christians.

Finally, several well-known persons were

arrested, and to force them to reveal the names of imaginary Comitadjis

(Members of secret organizations, here obviously for the overthrow of

the Turkish Government) and to reveal the places where they had hidden

arms, unmentionable tortures were inflict upon them.

This made me so apprehensive that I advised my

father to call upon the local head of the Committee of Union and

Progress, one Parmaksis Zade Sheikh Muslim, who was acting mayor, and

an associate of my father's in business. To him my father

confided his intention of leaving for Aleppo with his family, but

Sheikh Muslim reassured my father, saying:

"Do not worry; you have nothing to fear. In

case of danger I shall know how to get you away without difficulty."

My father was comforted by his words, but I

was still very doubtful and anxious, for I knew to the bottom the

character of the unspeakable Turk.

The continual passage of the convoys through

the town caused the Christians to live in a state of great anxiety.

One day the Chief of Police called upon the

Armenian Bishop, and ordered him to summon his flock to the Cathedrals

he wished to address them. The bell was rung, and all the people ran to

the Cathedral, filling it. Then the Turkish Commandant entered,

harangued the crowd, and in the name of the Government ordered them to

deliver up whatever arms they possessed under pain of suffering the

same fate as those perishing in the convoys.

"If you obey," he added, "not one of you will

be interfered with."

The Commandant with the Bishop then proceeded

to Garmush, a large village of five hundred Christian families,

situated about an hour and a half from the town, where he repeated his

harangue. Whereupon the National Council assembled immediately at the

Bishop's residence and discussed the advisability of surrendering

weapons. Treachery on the part of the Turkish Government was feared,

and the Council was divided in opinion. Bishop Ardawart, seeing danger

imminent, implored his flock to yield their arms, in order to appease

the anger of the Turks.

"I am ready to sacrifice myself, if

necessary," said the prelate, kneeling before his flock in tears.

Touched by his words, his hearers decided

unanimously to obey, and next day carts carried from the church to the

Governor's house rifles, revolvers and other arms which had belonged to

the Armenians. Unfortunately, a number retained their better weapons.

Knowing the Christians to be disarmed, the

Turks began their foul work. First of all fifteen or twenty prominent

men were arrested and thrown into prison, and their houses, that of the

Bishop and the Cathedral, were confiscated. All papers, books and

registers were taken to the Governor's house to be examined minutely;

and corners of the Cathedral and the Episcopal residence were dug up in

search of arms. Gradually, all men of influence were arrested,

imprisoned, and subjected to long inquisitions, during which they were

flogged until blood was drawn.

Special envoys with full powers arrived at

Urfa from Constantinople to direct the tribunals, and were entertained

as the guests of ex-deputy Mahmoud Nedim, a bloodthirsty man, all

powerful in the province. Bishop Ardawart, himself, and several of his

priests were soon arrested and taken to prison. Panic reigned among the

Christian population.

As for the Moslem civilians, they markedly

avoided the society of the Christians, and held secret meetings at

night, their sinister looks showing that they were hiding some tragic

plan. 'If approached for help, they answered that they could not mix

themselves up' in these matters, and declared definitely that it was

impossible for them to offer protection or shelter to a Christian. Such

action had been forbidden formally by the Government. In fact, all

Turks had been made to swear in the Mosques on the Talak (A

characteristic Turkish oath, by which the swearer pledges to divorce

his wife if it be proved that his statement be false, or that he has

broken his oath) that they would give no assistance to the Christians.

One evening a police agent, accompanied by

several soldiers, knocked at our door, and when we opened, announced

that he had come to search the house.

Three days before, two Armenian villagers had

become our guests, since they were our employees and helped in

our transport of cereals. In Syria, and especially in Lebanon, business

was limited to trade in foodstuffs, on account of the war. Urfa, being

an agricultural town, my father, among others, exported cereals to

Aleppo and to Lebanon. According to an old custom, peculiar to this

country, villagers in the employ of merchants or farmers, when they

come into town, become their guests, and are lodged and fed by their

masters; in many houses, indeed, rooms being set apart for this

purpose. (The very same custom prevails today in the wheat belt in our

Western States)

Not knowing what was happening in the

provinces, we had no suspicion of the danger we were running in

receiving these people into our house. Nor did our guests tell us of

what was going on in the country from which they had come.

Nevertheless, as a matter of prudence, my father, before leaving for

his office the day after their arrival, suggested to my mother that she

should advise them to seek lodgings elsewhere. The poor villagers,

unwilling to leave us, remained yet another day, and made up their

minds to go only when my mother insisted. Next morning they left, to

return again in the evening and spend the night with us, and had not

left the house when the police found them biding in the corner of the

kitchen.

It was not until later that we learnt that the

village where the poor people had lived -Hochine, a dependence of the

Sandjak of Severek - had been entered by soldiers and Kurds, who had

massacred nearly every inhabitant. A few men escaped to the mountains,

among them our two villagers, who later came to us.

They were arrested, of course, and taken to

prison.

My mother was alone in the house when my

father returned at seven in the evening, at which time a policeman

called and arrested him, on a charge of having given refuge to two

insurgents. It was even alleged that he had relations with the enemy,

and was exporting cereals to them via Lebanon.

One of my brothers at once ran off to my

father's intimate friend, already mentioned, Sheikh Muslim, the head of

the Committee of Union and Progress, gave him an account of what had

occurred, and implored him to intervene. Although the official

reassured him, my brother went to the Chief of Police, likewise a

friend of my father's, who a fortnight before, in company with Sheikh

Muslim, had accepted our hospitality and spent the evening at our

house. The Commandant promised to release my father the very next day,

whereupon my brother returned at a late hour and calmed the family.

Next day he went again to our Turkish friends,

who, this time, declared that we must have patience for two or three

days, since to liberate my father immediately would only attract public

attention, inasmuch as none of the influential Armenians had been

released. These repeated promises led us astray and prevented us from

taking recourse to other and perhaps more practical methods. Several

days passed, fruitful of no more than promises. Hadji Bekir Bey, father

of Sheikh Muslim, an octogenarian millionaire, who occupied the

position of Honorary Persian Consul, and who held my father in great

esteem, sent every day to obtain news and begged his son to make every

effort to save him.

A month passed, and the definite promises of

the earlier period became evasive. My father's friends, now seeing

themselves powerless to save him, ended by declaring that it looked as

if someone in high authority was opposing his release. They would not

name the person whose interest it was to ruin my father, although

Sheikh Muslim admitted to us later that it was no other than the

ex-deputy, Mahmoud Nedim, the terror of the countryside.

Six months before, Mahmoud Nedim had had a

difference with my father, and became his enemy. This man had a large

property at Tel-Abiad, an important station of the Baghdad Railway,

forty kilometers from Urfa, a point from which cereals are exported on

a large scale. Here, also, it happened that my father kept on hand a

large stock of empty grain sacks.

Nedim had harvested his crops and wished to

send them to Aleppo for sale, but was unable to procure sacks, which

had become rare and costly, owing to requisitions by the Government.

Knowing that my father had some stored at the Railway Company's depot,

he went to the official in charge, unknown to us, and asked for them,

saying that my father had taken his sacks under similar circumstances,

they being intimate friends. Either of his own free will or through

fear of the consequences if he refused, the storekeeper handed over

several hundred sacks, which belonged to my father.

My father soon learnt of the loss of his

sacks, which did serious harm to his business, but in view of the

accomplished fact, he said nothing. Later he requested payment for the

sacks-a rather large sum in itself. Nedim was deaf to the appeal.

Several months passed! Eventually my father encountered him at a

meeting of the influential men of the town, and, tired of waiting,

asked him to settle the matter. This his debtor considered a personal

affront, and in an insulting manner refused to pay. My father,

outraged, expostulated indignantly, and left him.

Now, it was this man, Mahmoud Nedim, who was

acting as host to the high officials sent from Constantinople to take

charge of the persecution at Urfa. It was his influence with his

powerful guests, which was stultifying the efforts of my father's old

Mohammedan friends, Sheikh Muslim and the Chief of Police, to secure

his release.

Arrest followed arrest, and Sheik Safwet, a

deputy of the town, went to Diarbekir in the infamous role of

instigator of a Djehad. (A

religious or "holy" war)

The Christians of Ourfa were terrified, as

well they might be, and in desperation and in the hope of saving their

men folk, the women cast themselves at the feet of these officials and

tried by every means in their power to soften their hearts. The

Tchettas patrolled the town armed to the teeth, and watched the

Christians with sinister intent, pursuing those who tried to escape to

the mountains to join the deserters from the army.

As an example of the barbarity of these

Tchettas chiefs I will digress here for a moment to repeat an incident

that was related to me by Mr. Demarchi, controller of the Ottoman Bank

at Urfa, who is a friend of mine. He was attending an open reception in

the Governor's official residence upon one occasion when he saw one of

these men in heated discussion with the commandant of the city, an Arab

from Damascus. As he watched, he saw the Tchetta box the ears of the

commandant and then draw his revolver to shoot him.

Only the swift intervention of the Governor

himself saved the soldier's life, and the weakness of the Turkish

Government is manifested by the fact that instead of punishing the

chief the Governor pacified him, adopting the friendliest attitude

towards him, as though he himself were afraid of similar treatment;

though the Turk continued to hurl insults upon him and all other Arabs.

A commission charged with the trial of those

detained in prison arrived at Urfa from Aleppo; whereupon we hastened

to call upon the President of the Court, and endeavored to gain his

sympathy by every means in our power. He told us that my father, being

innocent, would be released without delay, and he repeated this to my

mother when she, too, sent to him.

In the meantime many of the Armenians decided

to send a petition to the Governor, informing him that they intended to

embrace Mohammedanism, which had no effect whatever upon the Turkish

chiefs.

From the date of the arrival of these brigand

chiefs matters took a grave turn. No news came from the outside.

Letters, which had been sent to our cousins, the Roumis, at Diarbekir,

the sons of the former dragoman of the French Consulate, were returned

to us, marked "Absent."

We learned later that the Roumis had been put

on a raft on the Tigris, with the first Diarbekir Convoy, and had been

murdered en route.

The manager of the Ottoman Bank of Diarbekir

had arrived in great haste some days before this. Utterly

panic-stricken, he would tell us nothing of what he had seen. He had

undergone many dangers on the road, and remaining only for two days,

during which time he was concealed with Mr. Demarchi, he hastened to

Aleppo.

One day a rumor was spread that a soldier had

been killed by a bullet fired by one of the Armenian refugees who had

taken to the mountains. Thereupon, even greater hostility began to be

shown to the Christians. As the body of the soldier was being taken

through the streets, those who accompanied it made fanatical

demonstrations, and would have stoned a priest whom they encountered

had he not taken refuge in the barracks. This was Father

Wartan, who later, after three years' imprisonment, was unjustly hanged

at Adana, although the Armistice had already been declared.

Meanwhile, the Turkish soldiers in charge of

the convoys returned, their fell work done and their purses filled with

the pieces of gold they had taken from those whom they had deported,

and wantonly put to death.

During this time my father was confined in the

part of the prison reserved for those under sentence. There he soon

contracted dysentery and, very much reduced in strength and needing

proper care, begged us to use every possible means to procure his

release. The influential Turks who claimed to be his friends were

unwilling to intervene. It was tile Arabian Commandant from Damascus,

the one whom the Tchetta Chief had struck in the Governor's mansion,

who, at the request of a friend, went to tile captain in charge of the

prison, and asked him to remove my father to a place of less severe

confinement.

Meanwhile, the arrests continued, and became

the sole occupation of the Government officials and the police. For

hours, the head of the telegraph office remained at the instruments,

his anxious and worried expression showing the importance of the secret

orders he was receiving. All Christian officials were discharged, and

the Christian members of the palace force were degraded and dismissed

with contempt. The hatred of the Turks for the "Gaour" (Infidel)

increased, their looks became blacker and blacker, and the

fear of the Christians increased with the passing of time.

The Turkish populace now openly menaced the

Christian citizens, with the connivance of the police, calling them

traitors, adopting a threatening attitude and seeming to await the

signal for assault.

At night, the dwellings of rich Christians

were invaded, when a thoroughbred would be appropriated, or whatever

else of value pleased the robber. If the owner resisted, shots were

fired, and in the end he had to submit.

We now lost all hope of seeing my poor father

released, and I, myself, avoided leaving the house, so intolerable did

I find it to face the openly expressed hatred and scorn of the Turks.

One day I had occasion to go to the Ottoman

Bank on business, and went out of my ordinary route so as not to pass

the Government Building, wishing both to avoid black looks and to spare

myself the pain of seeing the prison where my poor father

languished. Although short, my journey seemed long to me and fearing

insult or pursuit, I walked more quickly. On arriving at the Bank I

knocked at a door on the first floor, and found myself opposed by a

sentry, who hitherto had shown me every respect. He asked me

impertinently whom I wished to see.

"The Manager", I replied.

"He is not here", he said.

"I shall wait for him," I answered.

On entering, I found neither M. Savoye nor my

young brother, who was an accountant. Two minutes later the guard

entered and said insolently, "There is no one here. It is forbidden to

wait here. Get out!"

Keeping quite cool, I told him I required to

see the Manager, whom I should ask if he, a mere sentry, had the right

to act as he had done. My reply irritated him and he advanced towards

me angrily. I then made my way to the door of Mr. Savoye's apartment,

which was in the same building, entered and met Madame Savoye, whom I

asked if her husband was there. She replied in the negative, and

noticing that, in view of the grave circumstances of the time, my

presence troubled her, I told her in two words of the gross rudeness of

the sentry. I then asked to be allowed to leave by her back door so as

to avoid a scene which might easily have fatal results for me, and

hurried off, thinking sadly of the unhappy lot of a Christian in Turkey.

Some days before this incident, two well-known

deputies, Zohrab and Wortkes Effendis had arrived from Constantinople.

After being received with honors by Haidar, the barbarous governor of

the town, and invited to his table by the hypocrite Mahmoud Nedim, they

were foully assassinated by Tchettas on the road from Diarbekir to

Sheikhan Dere. Shortly before this, Nakhle Pasha Moutran of Baalbek,

after being spat upon in the streets of Damascus, had been taken as far

as Tele Abyadh, and put to death.

Police Commissioner Chakir, brother-in-law of

Mahmoud Nedim, made use of the occasion to fill his own pockets. It was

his custom to order the arrest of a Christian, liberate him on receipt

of a bribe, and then re-arrest him two days later. Whoever arrived,

exile, prisoner, or one who had been deported, Chakir always found a

means of getting money out of him.

Later, in the Prisoners' Camp at

Afion-Kara-Hissar, I heard of one instance in which he failed.

Major Stephen White, an Englishman, who had

been captured on the Suez Canal and taken to Urfa with another officer

of the Egyptian Army, told me that this same Chakir, learning that he

had received a sum of money from his mother in England, tried his best

to obtain a share of it, but in vain. Major White always alluded to

Chakir and Nedim as the outstanding ruffians in the massacres of Urfa.

One morning, the news spread that fifty of the

more prominent prisoners had been taken after midnight to Diarbekir.

The anxiety of my home may be imagined! Was my father of the number? We

rushed off to the prison to find out. No, he was still there, and was

yet hopeful, for he had no suspicion of the terrible fate, which

awaited him. Little did he dream that his wife and eight children would

soon be weeping at his tragic end and he the victim of a shameful

injustice.

We ran to the houses of the chief friends of

our family.

"Have mercy, Muslim Bey! Save our father, your

old associate! Save your friend, your brother! He is going to be

deported and we shall lose him," with tears in his eyes, cried my

younger brother, Emine, who daily grew thinner and paler, by the fear

of losing his beloved father.

But the chief of the Union and Progress

Committee remained mute, saying nothing, doing nothing. We could not

make out his attitude. He was probably obeying some order he had

received. Everything, even one’s best friends, had to be sacrificed for

the Committee.

During the night, a new convoy, in two

sections, was sent towards Diarbekir, the victims bound arm to arm. One

or two hours outside the town, near Kara Koupru, they were shot in cold

blood, and their bodies left on the road for the ravens and the wolves.

Although they could not precisely know what

had happened to their menfolk, the families of these martyrs

experienced the wildest apprehension and grief, and the hearts of the

mothers, wives, and daughters told them that their dear ones were no

more; a foreboding which was confirmed by the hypocritical looks and

smiles of the murderers, who in the hope of further bribes, came to

reassure the relatives that all was well.

More and more anxious as to the fate of our

own dear prisoner, we returned to the prison. Alas! We were too late.

My father, a follower of no party, innocent of political crime,

absorbed in his family and his business, loved and esteemed by all, had

been taken along and slaughtered without the semblance of a trial. He

was mourned even by Turks, and his friend Hadji Bekir, the leading Turk

in the place, shed tears on learning that he had been done to death.

A person who saw him being deported told us,

two days later, that my father was one of a group of thirty led in the

direction of Diarbekir. He delivered to us a scrap of paper upon which

the head of our family had scribbled by moonlight, with trembling hand

the following:

"We are leaving for Diarbekir. Pay Monsieur

N_____ the sum of… which he has lent me."

The note was signed with my father's

signature. He had then wept, according to our informant, and said: "I

am patiently awaiting my fate. My life is of little importance to me!

But my children! What is to become of them?"

Taking out his watch he handed it to the

messenger to be delivered to Sami, his youngest child, then a boy of

nine, and requested him to keep it in remembrance of him.

CHAPTER II

My Escape

We received the news of my father's murder

early in August 1915. That very evening one of my brothers, Djemil, who

had come from Aleppo to Urfa some days before, fled on horseback with

some companions back to Aleppo in fear. At Tell Abyadh he encountered

Sallal, the son of an Arab Sheikh who was a friend of the family, whom

he begged to return to Urfa with our horses and rescue the rest of the

family.

Three days later some English civilian

prisoners employed at the Ottoman Bank in the Administration of the

Public Debt, obtained permission to leave the town, and despite the

risk they ran, very kindly took with them in their carriage two of my

brothers, George, aged thirteen, and Fattouh, who was two years older.

Thus there remained in Urfa only my two youngest brothers and my

mother. Soon after Saltal, accompanied by Aziz Djenjil, a very brave

and devoted Christian employee of ours (dressed as a Bedouin) arrived,

and took the rest of the family, excepting Emine and me, to Tel-Albiad.

The stationmaster, another friend, put them in the train for Aleppo.

My mother, before leaving, sent a large part

of our furniture to her cousin, M.P. Ganime. Twenty days later it was

all looted by the Turkish populace.

My brother Emine and I remained at Urfa, where

the arrests continued, several of my friends and acquaintances being

taken and massacred.

On August the 19th a police agent with some

soldiers went to the house of an unfortunate Armenian to take him into

custody. Determined not to be trapped without making an effort to

defend himself, the man knowing that arrest meant death, shot and

killed the policeman and two soldiers. Armed Turks rushed through the

markets and streets, killing all the Christians they encountered. Some

managed to save themselves by hiding. Many took refuge in the

presbytery. My brother Emine, who had been obliged to go to the bank,

had the greatest difficulty in reaching me.

The streets were strewn with the bodies of the

six hundred Christians kille4 that night, and their blood literally ran

in the streets. The murderers steeped their hands in the steaming gore

and made imprints on the walls that bordered the streets. In this

frightful orgy English and French civilians, some of whom had been

interned at Urfa a month previously, also perished. Several of them who

happened to be in the streets at the moment of the outburst were taken

back by soldiers to their homes, lest the populace should fall upon

them by error. One of them, a Frenchman of Aleppo, M. Germain, had his

throat cut by the ruffians. A Maltese who was pursued and stoned took

refuge in the house of a Christian and was saved.

Two hours after the firing had ceased, I

mounted to the roof to see what was happening in the streets, and

noticed that the police, instead of calming the fanaticism of the

Turks, were inciting them to renew the massacre. Not until all the

Christians who were discovered in the shops or in the streets had been

killed was an order issued to end the carnage.

In the evening, all was quiet, but no

Christian dared show himself and the Armenians prepared to defend

themselves, barricading their premises. But the cowardly murderers were

afraid and attempted no further harm.

The next morning I heard cries in a little

lane near our house where there was an oil press. A moment later I saw

a Turk named Moutalib leave his house and make off in the direction of

the cries. Half an hour later I saw him return with his dagger stained

with blood, proud of his work, laughing and shouting: "Hiar Guibi

Kestim" (I chopped him up like a cucumber!). The

victims were two workmen who had hidden themselves in the oil press.

The Turks, under pretence of saving them, had succeeded in making them

come out into the streets, where they cut their throat, stamped on

their heads and dragged their bodies along the ground.

It was the duty of the Jews to drive carts and

pick up the dead bodies and throw them outside the town to the dogs and

birds of prey (This sinister duty had been imposed upon

the Jews by the Turks during the massacre of the Christians.)

In the afternoon, a soldier, accompanied by

the porter from the Bank, came by order of the Manager, M.

Savoye, for my brother, Emine, who returned to the Bank, where he

resided. There he was safe, the establishment being guarded by the

police.

Towards ten o'clock I saw the Governor himself

Haidar Bey, passing through the streets with the Chief of Police, to

show that he had no official cognizance of any disturbance, and to

prove to the Christians that order had been restored, and that they

could come out without fear.

M. Savoye, I should like to state, displayed

the highest courage during these terrible days in the way he helped our

family in our extremity. We owe him the warmest debt of gratitude.

Sallal, our Bedouin friend, had promised to

return as soon as he had taken my mother and brother to a place of

safety and the day after the massacre he came to see me at the

Presbytery. Being now alone, I was in danger of arrest every moment,

and decided to take to flight. It was a hazardous undertaking, but I

was determined to make the attempt. Urfa had become a very hell!

Muffling myself in Bedouin robes, I prepared to leave with Sallal.

The town was not yet quite calm, and

Christians remained shut up in their houses, fearful of new out-bursts,

although every one of prominence among them had already been executed.

About five hundred Christian soldiers employed on the construction of

roads near the town had also been put to death. One alone escaped. In

giving me an account of his experiences, he declared that the officers

were keeping in their tents young Christian girls, stolen from the

convoys. He spoke in particular of one very beautiful Chaldean girl

from Diarbekir, kept as a prostitute, and passed from one Turk to

another. By a miracle the girl survived and is living today in Urfa.

At seven o'clock of the evening of August the

21st, 1915, Sallal came, and I bade farewell to my friends, including

Father Emmanuel Kacha, who stayed behind with his family.

Hurrying through the almost deserted streets,

we reached the house of one of my relatives, where I donned the costume

of a Bedouin. This consisted of a long wide-sleeved shirt of white

linen, an "aba" (a sleeveless cloak of camel hair) and on my

head I wore a "tcheffie" (a headdress, square in shape, with long

fringe, surmounted by an " agal" a kind of camelhair crown). As I spoke

Bedouin a little, I was not likely to be recognized. Near the edge of

the town we met a police agent and two soldiers, who seemed to be

waiting for us. The valiant Sallal, who was armed with a large sword

and a revolver and was a man of great height, advanced fearlessly. We

both salaamed profoundly and passed on, our salute being returned. - A

hundred yards further on, my companion remarked that we had just had a

very narrow escape.

At the house of a friend outside the town we

found our two horses, and took the road to Tell Abyadh.

The moon shone softly down upon us, and my

companion, happy to have saved a friend from the claws of the Turk, and

moved by the beauty of the scene, burst like a troubadour into the most

beautiful Arabic verse.

Three hours later, as we were about to halt on

the bank of a river, two horsemen appeared and rode towards us. Sallal

told me to take my horse and keep at a distance. The newcomers turned

out to be a Turkish tax collector and a soldier, and after asking

Sallal for news of the town, they rode on.

Farther along, we met some Arabian horsemen,

among whom was Sallal's brother, a despotic chief with whom he was on

bad terms, Sallal was in the happiest of moods. While passing us his

brother, bent on loot, called out, "I quite understand! You are busy

saving another Christian."

At these words I was alarmed, but Sallal,

always resourceful, replied with a joke, and the danger passed.

At twilight we came to the village where my

companion lived, and where I accepted his hospitality for a day, his

mother and brother welcoming me as if I were a relative.

We had intended to continue our journey

without delay, but several Turks inopportunely arrived. They thought me

a Kara-Guetch, one of a marauding Arabian tribe, then in revolt, and

asked Sallal why he had taken me under his roof. Fearing that it might

be discovered that I was a Christian, Sallal had his brother take me to

a distant spot in the country, and the Turks left, threatening to

report him to the Kaimakan (Lt. Governor).

On my return to the village I found everyone

in a state of alarm and terror, declaring that Sallal had jeopardized

their safety' so he mounted his horse, told me to do likewise, and we

rode at a gallop to Tell Abyadh. There I met several of my

parishioners, who were in the service of the Baghdad Railway Company,

and was taken to the house of one of them, M. Youssouf Cherchouba, who

received me in a very friendly spirit. Then, wishing me a safe journey,

my Arab protector said good-bye, and returned to his own home. Day had

not yet broken. Cherchouba told me in a low voice that persecutions had

begun at Tell Abyadh and that he was very anxious.

I knew the telegraph operator of the Railway

Company, M. Dhiab, and on expressing a desire to see him, was taken to

his office by George Khamis, one of my Chaldean parishioners.

Circassian Guards, of whom the Railway employees were in deadly fear,

were posted at the station. Had they suspected me, I should have found

myself in considerable danger. The operator was very much astonished to

see a Bedouin, and wondered what one could want with him. He was still

more astonished when he found that the Bedouin spoke and understood

French. He was the friend who had assisted to smuggle my mother and

brothers through, and it might be compromising for me to remain in his

office dressed as a Bedouin was unable to change, as Sallal had left my

clerical dress on the road, so I hid until the evening train left.

An Arab had been notified, and for baksheesh

(a bribe) hid me in a neighboring village, which the inhabitants had,

abandoned for the summer (evidently the winter home of a nomadic

tribe). There I waited alone, and, being very fatigued, fell asleep on

the floor in a tiny room, to awake at break of day, bathed in

perspiration, but very much the better for my rest and very hungry. An

hour later the Arab returned with some bread and "khather" (curdled

milk, sour milk) but the bread was so very bad that, hungry as I was, I

could not eat it.

When night came the Arab took me back to the

station, where I hid in a building until the arrival of the Aleppo

train. My friend, the telegraph operator, came to an understanding with

the conductor, receiving a guarantee that I should be taken safe and

sound to Aleppo for a stipulated sum of money, which I readily paid. I

was put aboard a cattle truck, which had not been cleaned since its

prior load had been unshipped, so gave off a very disagreeable odor.

The train stopped and through the crack in the

doors I saw a guard approach my truck. It was the conductor to offer me

a place in a first-class carriage. Because of my dress, I asked him to

let me travel third-class, but a brakesman, who noticed us conversing

and who suspected our agreement, at Arab Punar forcibly put me into an

open truck, during the absence of the conductor.

At this place we took on deported families of

English and French civilians, going from Urfa to Aleppo. At the next

stop, the first guard returned me to my compartment in the coach, which

was shared with some invalid soldiers and some Turks from Urfa. The

latter commenced to make fun of me, as is their custom with Bedouins,

but I pretended to be asleep. We arrived in Aleppo at ten o'clock the

next morning.

At Aleppo I hunted up my cousin, Faris, who

acted as storekeeper for the Railway, in order to ask him to direct me

to where my mother lived.

I asked a Mohammedan who was in the station to

show me where the company's store was located. He demanded baksheesh,

and when I had complied he condescended to point with his finger to the

particular depot. Faris had not yet come to his office, and in

accordance with the Bedouin custom, I took up my position in the shade

of a wall a short distance away and waited. He arrived ten minutes

later and, recognizing me gave a cry of astonishment. I made a sign to

him to keep quiet. Much moved at seeing me, he abandoned all thought of

work, and placing himself entirely at my disposal, conducted me to my

family, who, fearing to be molested by the authorities, had decided to

live in a house in the outskirts of the town. To get there we to pass

through many narrow and winding lanes. Imagine, if you can, the tears

of delighted surprise with which my mother, who had begun to fear that

I had shared my father's tragic fate, welcomed me.

I had been a month at Aleppo, assisting the

Chaldean parish priest of the town, when I received a telegram from His

Beatitude, Thomas Emmanuel, the Chaldean Patriarch of Babylon,

suggesting that I should go to Constantinople as a Chaplain to the

English and French prisoners of war in a Turkish camp.

CHAPTER III

The Fate of Urfa

The unhappy town of Urfa suffered one of the

saddest fates ever recorded in history. The day after my departure,

August the 23rd, the Governor sent an order to the Christians to leave

their houses and carry on their businesses. As soon as they obeyed, a

second order commanded the Armenians to leave the town. Knowing what

this meant, the unfortunate' people refused to obey. Already doomed,

they preferred to die in their homes than perish in the desert. The

government resorted to force to make them leave, and the Armenians

resisted, till finally, on September 23rd, a pitched battle was fought.

Although it lasted a week, the Turks were unable to penetrate the

Armenian quarter. The Governor sent to Aleppo for reinforcements to put

down the so-called "insurgent" Christians and Fakhri Pasha soon arrived

at Urfa at the head of an army supported by artillery. The Armenian

quarter was attacked, but the Turkish troops, in spite Of all their

efforts, were powerless to overcome the resistance of the brave

Armenians, who, seeing that in the case they had to die, defended

themselves, most valiantly. Several hundred of Turkish Soldiers were

killed in the course of the battle. Women and girls threw themselves

into the fray and assisted their menfolk to defend their homes, their

lives and their honor.

Fakhri Pasha then opened fire with his

artillery upon the Armenian quarter, and a bombardment commenced which

lasted a fortnight. Several English and French witnesses interned at

Urfa at the time told me s a German officer who had directed the fire.

A large number of combatants took refuge in the American Mission,

whereupon the Turks ranged their guns on the Mission and managed to

destroy part of the building. Through the breaches thus made, they were

able to penetrate the lines of the defenders, who were obliged to hoist

the white flag.

The bombardment had caused a conflagration,

which spread over a wide area, owing to the fact that many of the

Armenians, themselves, seeing death approaching, gathered in crowds in

their houses, and rather than give themselves up alive to the Turks,

set fire to their dwellings and perished in the flames.

After the inevitable surrender of the remnant

of the Armenians, the Turks gave freer play than ever to their innate

barbarity. Throwing themselves on the quarter, they put to the sword

ill the Christian men, women and children they met, looted everywhere,

and set aflame all that remained. The men still alive were dragged

along the Diarbekir road outside the town, as so many of their fellow

Christians had been before them, and were executed. Some women and

children were ranged on the edge of an abyss, stabbed and pushed over,

to be devoured by the dogs and birds of prey attracted by the odor of

the bodies.

The women and children who still survived,

about two thousand in all, were shut up in an immense building, known

as the " Millet Khan." Here they were the butt of Turkish

ill-treatment. Many of them died of hunger and of typhus,, which spread

rapidly. The corpses were taken to a distance and emptied into huge

ditches; living children cast in with the dead.

In the courtyard of the cathedral, ghastly

scenes took place, where heaps of bodies almost blocked the main

entrance, living and dead piled together; the death rattle of those in

their last agony distinctly audible from time to time.

And on one occasion, a large number of men and

women were publicly hanged, in the presence of the rejoicing Turkish

populace.

Thus fifteen thousand people were done to

death in a few days.

The American Missionary, Mr. Lesly, with whom

a certain number of the Armenian defenders had taken refuge, was

summoned to appear before a courtmartial on the charge of having taken

part in the revolt. One day, on leaving the court, they found him dead

on the road. A paper was found in his pocket in which he stated that he

had not been implicated in the matter of the Armenian revolt.

CHAPTER IV

My Prison Experiences

At the beginning of November 1915, a

telegram from His Beatitude, Emmanuel Thomas, the Chaldean Patriarch of

Babylon, suggested to me that I should go to Constantinople as Chaplain

to the Allied Prisoners of War. I set out, furnished with a permit from

the Governor of Aleppo. At the beginning of November 1915, a

telegram from His Beatitude, Emmanuel Thomas, the Chaldean Patriarch of

Babylon, suggested to me that I should go to Constantinople as Chaplain

to the Allied Prisoners of War. I set out, furnished with a permit from

the Governor of Aleppo.

Pope Benedict XV, after several months'

negotiations, had obtained from the Turkish Government permission for

priests to visit the Prisoners' Camp. They were, however, to be

Chaldeans.

On my arrival at Constantinople, the War

Office granted me the requisite papers, and on December the 15th I left

for Afion-Kara-Hissar, a concentration camp for English, French and

Russian prisoners. I was accompanied by a young and very devoted priest

from Smyrna, the Reverend Moussoullou, who, claiming to be a Chaldean

by origin, obtained permission to replace the Chaldean priest

originally appointed to assist me, but who was unable, by reason of his

advanced age, to undertake the long journey from Aleppo.

It was an opportunity for my colleague to

rejoin his parents, who were then at Afion-Kara-Hissar, and whom he had

not seen since his ordination.

We arrived at Afion on December 17th and were

met at the station by a Turkish officer, who conducted us to the camp

in which we were to be interned.

I pass over here much detail of which I hope

to treat in the near future in a separate work, entitled: The Allied

Prisoners in Turkey."

When

I had been there about three or four months, that is to say, early in

the spring of 1916, three British Naval officers escaped. The

Commandant of the camp, Assim Bey, a Staff Colonel, was dismissed, and

replaced by the notorious tyrant, Mazloum Bey, a conscienceless, cruel

and despotic creature of the Committee of Union and Progress. His

assistant, Captain Safar, was no less cruel. Both of them took the

greatest pleasure in worrying and torturing the prisoners. When

I had been there about three or four months, that is to say, early in

the spring of 1916, three British Naval officers escaped. The

Commandant of the camp, Assim Bey, a Staff Colonel, was dismissed, and

replaced by the notorious tyrant, Mazloum Bey, a conscienceless, cruel

and despotic creature of the Committee of Union and Progress. His

assistant, Captain Safar, was no less cruel. Both of them took the

greatest pleasure in worrying and torturing the prisoners.

Several months passed. Towards the end of

September 1916, Mazloum gave orders for a general search to be made in

the camp, and the belongings of the officers were searched with

meticulous care. Of this we learnt from Dr. Brown, an Englishman, who

came to look after the prisoners.

Shortly after this, Major Ahmed Hamdi, a

reserve officer and a relatively good and honest man, came with Captain

Safar to warn me that I was to leave the camp and live in a house near

that of the officers. I left my quarters on the morning of October the

2nd, two British prisoners being kind enough to carry my luggage. The

new quarters assigned to me had formerly been occupied by Christians,

who had been exiled or massacred.

The evening being cool, and having a few

minutes’ leisure, I took a constitutional walk, up and down a space of

a hundred yards before my door, in company with a kindly and

sympathetic British naval officer, Commander Goad, and a French

lieutenant, named Otavic, who had fought at the Dardanelles. Being

desirous of familiarizing myself with English, I chatted a great deal

with my companions.

In accordance with the routine of the

concentration camp, we returned to our respective quarters at 7

o'clock. Five minutes later jailers made their usual round and doubly

locked our doors with their large keys.

Absolute silence reigned in camp, each man

being shut off from his fellows. My orderly, a faithful Indian

prisoner, named Enadji, brought me my dinner. As I ate, I thought of

the hundreds of prisoners whom I had been obliged to leave.

At 8 o'clock, I was glancing through a Turkish

daily newspaper, my orderly was sleeping soundly in his quarters, when

the lock turned and the hall-door opened. A knock sounded on the door

of my room! Leaving my newspaper, I arose and opened the door. Nebzet,

a Cypriot Turk, who held the post of English interpreter, entered and

told me very politely that Mazloum, the Turkish Commandant, wished to

see me.

Putting on my overcoat, as it was chilly, I

went out with the interpreter, and, expecting to return shortly, I left

my lamp alight, and did not even disturb my Indian orderly.

I suspected absolutely nothing, and I remember

asking the interpreter for what special reason the Commandant wished to

see me at this hour. He replied that be knew nothing about it.

"I hope he is not angry with me again," I

remarked, jokingly, as he had been many times.

"I do not think so," said Nebzet. "As a matter

of fact, be was very gay this evening."

On the way to the Commandant's house the

interpreter chatted familiarly and almost cordially, and, on our

arrival, deferentially stood aside for me to enter, first. I seated

myself on the nearest chair, but Nebzet pressed - or rather obliged -

me to take the post of honor, offering me a cigarette, which, not being

a smoker, I declined. He then left me; and, two minutes later, the

Commandant, clad in his night shirt, entered with Major Ahmed Hamdi,

Captain Safar, Nebzet and a companion whom I did not then know, but

whom I found later to be an influential citizen of Afion-Kara-Hissar,

named Khalil Agha. The Commandant came towards me and with the smiles

and gestures of a comedian shook hands most graciously and offered me a

seat reserved for honored guests. Then addressing the companion I did

not know, he said:

"Here is our very great and most sincere

friend."

After an exchange of greetings, as we sat

down, a long silence ensued, until the Commandant broke it by saying to

the interpreter:

"Now, bring the letter and read it."

Nebzet read the following words, which I quote

from memory:

"Mon bien cher Commandant."

As I heard these words, the situation became

clear to me. This was a letter I had addressed to the French Captain of

the............ eight months previously, when the French prisoners of

war had left our camp. I had wished to follow them to Bozanti, in the

Taurus Mountains, where they were to be employed on the construction of

an important tunnel on the Bagdad Railway. At the time, the camp

commandant was Assim Bey, with whom the senior French officer was on

good terms. When almost all the English and French prisoners had left I

requested Assim Bey to allow me to accompany them, as was natural,

writing as well to Monsieur X----- and begging him to use his influence

with Assim to this end. At the same time, I recollect, I expressed my

regards for the prisoners and towards their country, and also my wish

to be able to make myself of use to them.

The Turkish Commandant had a grievance against

me, and made this letter a pretext for taking his revenge.

Four months before, it is true, I had

disobeyed his orders in regard to the burial of a Russian doctor, who

had died of typhoid fever. My church did not permit me to conduct the

funeral services for those professing another religion, and I had tried

to excuse myself to Ahmed Effendi, who had come to me with an order

from Mazloum to read the last rites for this Russian. I refused, but

gave no reason for doing so, fearing I should be misunderstood. The

officer re tired without insisting.

The next day, the Commandant expressed his

displeasure to me in person.

The same difficulty arose on two other

occasions, when again I refused to obey, and again evaded giving my

reason. I was exceedingly loath to wound the susceptibilities of the

prisoners, all of whom I regarded as brothers in adversity and between

whom I never made distinctions other than those laid down by the canons

of the church. But in the end, Commandant Mazloum insisting, it was

necessary to give the true explanation.

Mazloum had become still further exasperated

when, at Easter, on his wishing to prevent my going to see the officer

prisoners, I wrote to him that it was my duty to put myself at their

service, and that, if lie made difficulties, I should send in my

resignation to Constantinople.

Shortly after this many English prisoners

arrived from Kut-el-Amara, a Russian doctor was assigned to their care,

although he knew no English. As I had learned to speak the language a

little, I offered my services as interpreter. One day Mazloum came to

the prison quarters and, seeing me with the doctor, expressed his

disapproval. He told me that I had nothing to do with the Russian